Tags

Barry Fantoni, Christine Keeler, Lewis Morley, Mandy Rice-Davies, Michael Ward, National Portrait Gallery, Pauline Boty, Profumo Affair, Scandal 63, Solihull, Stephen Ward, Tom Blau

Scandal ’63, currently a wall display in Room 32 of London’s National Portrait Gallery, takes its name (and logo) from journalist Clive Irving’s account of the Profumo Affair, published fifty years ago.

The display is divided into small sets, depicting the major figures, the trials and how the scandal influenced art, film and satire. John Profumo, Minister for War in Harold Macmillan’s Tory government, is seen at his wedding to actress Valerie Hobson in 1954.

The other photos of Profumo are rather ironic. He is shown dancing the Twist with his elegant wife in 1962, boosting his image as a relatively young and glamorous politician. It’s easy to imagine why, in contrast to the staid Macmillan, he was once perceived as a possible future Prime Minister. And in a publicity stunt he may have regretted, Profumo visits an army barracks to inspect female officers’ uniforms.

His last portrait is a photo-montage, combined with a picture of his erstwhile mistress, Christine Keeler. Though their names have been linked for a half century, they were never photographed together – and, in fact, never crossed paths again after the scandal broke.

Press photos were often wired, accompanied by details of time and place. Among the photographers who covered the Profumo Affair were Kent Gavin (later the Mirror’s royal photographer); John Deakin (best-known for documenting London’s art scene); and Horace Tonge, whose work has been featured in the Times archive. Unnamed others worked for news agencies like Keystone Press, and their photos were syndicated worldwide.

Dr Stephen Ward – the respected osteopath whose fall from grace began when he, perhaps inadvertently, brought the infamous couple together – was also a gifted portraitist. His haunting pastel sketch of Keeler was probably drawn around 1960, when he first encountered her as a dancer at Murray’s Cabaret Club in London’s West End. This portrait has a special resonance for me, as I used it on the cover of Wicked Baby, my novella about the events of 1963.

Christine Keeler by Stephen Ward, pastel, 1960 or 1961

After Ward became the ‘fall guy’ for the affair, his portraits acquired a certain notoriety, drawing his famous subjects into the headlines. Several were featured on the front page of a British tabloid newspaper, the Sunday Mirror, on July 28th – including Lord Astor, at whose Cliveden estate Ward rented a cottage. Profumo is said to have spotted Keeler (then just 19, and 27 years his junior) while she was taking a late-night swim during a party at Cliveden in the summer of 1961. Another portrait depicts Eugene Ivanov, the Russian naval officer whom Ward met after he was posted to London, at the height of the Cold War. Keeler, who was Ward’s flatmate at the time, claims she was briefly involved with Ivanov after meeting Profumo.

That fateful weekend is represented by a group photo, featuring both Ward and Keeler grinning by a swimming pool. They are joined by two of Ward’s other protégées – one is Sally Norrie, who would later testify against Ward when he was falsely accused of living off immoral earnings. On June 8th, 1963, the photo was published for the first time. The blonde on the left was erroneously identified as Mandy Rice-Davies, a friend of Keeler who would later play a role in the scandal. While Davies visited Cliveden as Ward’s guest on several occasions, she was absent that weekend – and in fact, she never met Profumo.

Ward at Cliveden with Keeler, Norrie and mystery blonde, July 1961

But this carefree interlude would soon end. Ward’s final days are represented by a series of press photos, showing him arriving at the Old Bailey with journalist Pelham Pound, who was acting as his literary agent; attending the muted reception of an exhibition of his portraits, which coincided with the trial; and leaving court with girlfriend Julie Gulliver on July 24th, 1963 – a week before his fatal overdose.

On June 9th, Keeler testified at the trial of her ex-lover, Lucky Gordon, who was charged with serious assault. She was photographed arriving at court with two other witnesses; her current flatmate, Paula Hamilton-Marshall, and their housekeeper, Olive Brooker. The case was later dismissed on appeal.

Keeler goes to court, June 1963

Gordon, along with another of Keeler’s former boyfriends, Johnny Edgecombe, was photographed on July 10th, arriving by car to testify for Lord Denning, who was compiling an official report. Their journey must have been tense, as the two men had previously brawled over Keeler in a nightclub in October 1962.

In her 1964 memoir, The Mandy Report (also known as My Lives and Lovers), Mandy Rice-Davies promised to reveal ‘the truth, at long last, about the snakepit masquerading under the title High Society’. Davies was one of the few who attended Ward’s exhibition, and two publicity shots from the same period illustrate her unshakable confidence.

Mandy Rice-Davies, 1963

In the first, she is the quintessential girl about town, sporting heavy eyeliner and coiffed blonde hair. She smokes a cigarette, and carries a handbag. The second was taken on June 17th, during to a visit to her parents’ home in Solihull. Once again, Davies is perfectly groomed in a white polka-dot dress, with her pet poodle on her lap. Perched on a sofa, Davies’s sly, knowing expression belies the demure pose; and after all, this would-be sophisticate was, not long before, the teenage mistress of slum landlord Peter Rachman.

Mandy in Solihull, June 1963

Mandy survived unscathed, whereas Christine found it tougher to live in the spotlight. However, one photograph, taken at the height of the scandal, ensured her a permanent place in our cultural history. It was taken at The Establishment; a Soho club which, for a brief period, hosted some of Britain’s finest up-and-coming comedians and musicians.

The shoot was in black and white. Artfully naked, Keeler sat on a backward-facing chair. Her face is in profile, and her expression is enigmatic: defiant, yet fragile.

Keeler’s iconic pose for Lewis Morley, 1963

Her photographer, Lewis Morley, was always somewhat puzzled by the success of the image. It became a symbol of the 1960s, but for both artist and model it was something of a mixed blessing. It was first published in the Sunday Mirror on June 9th.

Morley died on September 13 this year, leaving his photos and correspondence with Keeler, along with his other famous works from the era, to the National Media Museum in Bradford.

Movie poster, 1963

The photo session was arranged to publicise a film based on the scandal, in which Keeler was to star. It was eventually shot with actress Yvonne Buckingham. Keeler provided a short introduction, which was badly dubbed. She was photographed by Tom Blau in what was described as a ‘screen test’. She had been smuggled into the studio for filming.

Christine’s screen test, by Tom Blau

That November, Keeler was profiled in US film magazine, Modern Screen – featuring Blau’s stills and another from the Morley session. ‘Chris has always wanted to be a star’, the article read, adding that she ‘expects to make a mint from this movie.’

However, the film was never released in Britain, and remains obscure. It has been variously titled That Keeler Affair and The Christine Keeler Story.

Harold Macmillan, by Gerald Scarfe for ‘Private Eye’

Founded in 1961, Private Eye came into its own as the Profumo Affair unfolded. Its June 14, 1963 issue featured Harold Macmillan, in a parody of Keeler’s nude portrait by cartoonist Gerald Scarfe. The caption reads, ‘Only one man was in a position to cover up for his friends.’

‘That Affair’: cover art by Barry Fantoni

A caricature of Keeler herself – by another artist, Barry Fantoni – adorns the cover of That Affair, a satirical LP. Among the tracks are titles like ‘Dimbleby at Cliveden’, and ‘The Little White Lie That Jack Told’.

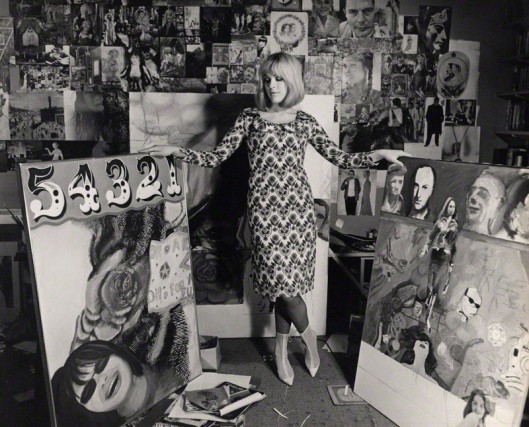

In the autumn of 1963, pop artist Pauline Boty began work on a painting, also called ‘Scandal ‘63’. An early version of the painting was based on a press photo of Keeler leaving her flat. Boty was photographed by Lewis Morley, and she later replaced the original Keeler image with his more famous pose. Profumo and the other men are reduced to a row of headshots above Keeler’s full body.

Unfortunately, the painting was lost after Boty’s tragic death in 1966, and only a few photos exist of the work-in-progress. She is currently the subject of a retrospective, Colour Her Gone, at Wolverhampton Art Gallery.

My sole criticism of Scandal ’63 is that it is rather a small display, and a catalogue is not available. Perhaps it could have been expanded beyond 1963, to explain why the Profumo Affair is still relevant today. It has nonetheless attracted a great deal of media attention, and is well worth seeing if you can make it to London by this Sunday, September 15th.

- Boty photographed by Michael Ward, January 1964

Related Posts

Hi Tara Marina..Many thanks for reviewing our Scandal 63 in its last few weeks. Unfortunately we had only the one screen on which to hang so the number of items and scope was necessarily limited but we would have loved to expand into the areas you suggest..maybe we can tour it elsewhere and enlarge in the run up to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s new musical. Please note Lewis Morley was born in Hong Kong and came to London. Its was only in 1971 that he left for Austrailia. Could you look at our Scandal 63 Blog on the NPG site and put your comment there so we can respond. Clive Irving lived in New York but popped in to say hello just after the opening!Thanks Terence

________________________________

Hi Terence, thanks for reading my review and letting me know about Morley, I’ve now corrected it. I’ll also visit your blog as you suggest. I enjoyed the display very much, and hope you can do more with it. All the best, Tara