Tags

Ann Karger, Conspiracy Theories, Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend, Do It Again, Frank Sinatra, Fred Karger, How Wrong Can I Be, Jacqui Warren Rigoni, Jane Wyman, Jay Margolis, Joe DiMaggio, Joe Schenck, John F. Kennedy, Johnny Hyde, Johnny Warren, Ladies of the Chorus, Love Happy, Marilyn Monroe, Mary Karger, Michael Reagan, My Maril, Natasha Lytess, Patti Sacks Karger, Robert F. Kennedy, Terry Karger

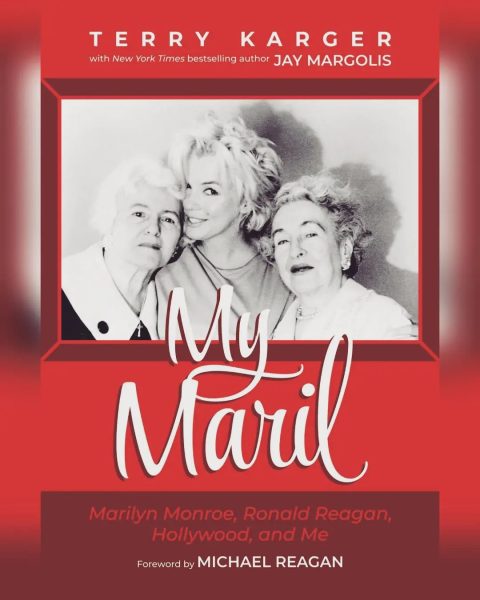

My Maril: Marilyn Monroe, Ronald Reagan, Hollywood, and Me is a new memoir by Terry Karger, daughter of Fred Karger, a composer, musician and bandleader who dated Marilyn in the late 1940s. Terry was Fred’s daughter from his first marriage. Marilyn remained close to the Kargers – especially Fred’s mother Ann and sister Mary – long after their relationship ended.

My Maril is published in hardback (and via Kindle) by Post Hill Press, a US conservative Christian imprint whose other titles include Edward Z. Epstein’s Frank & Marilyn, due for release next month. Karger’s ghost-writer is Jay Margolis, co-author of a conspiracy book about Marilyn’s death; and Terry’s stepbrother Michael Reagan provides a foreword.

Michael was Ronald Reagan’s son from his first marriage to Oscar-winning actress Jane Wyman, who became Fred Karger’s second wife in 1954. A year before their wedding, Michael had attended his mother’s birthday party at Fred’s home. He was then seven years old, and before the party, had visited a jewellery store with his twelve-year-old sister Maureen to buy a present for their mother. In the shop window was a silver serving tray imprinted with an image from Marilyn Monroe’s nude calendar shoot. He wanted to buy it, but Maureen wisely refused! At the party, Michael opened the door to guests and was dumbfounded to see Marilyn ringing the doorbell (fully clothed, of course.)

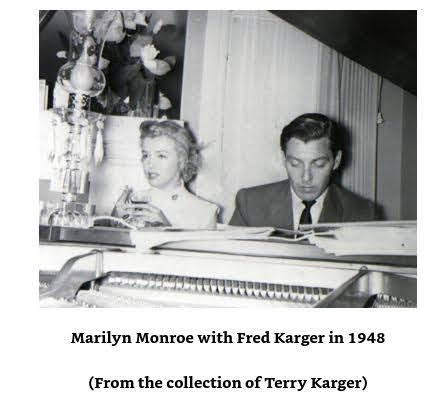

Terry was six years old when her father began dating Freddie Karger in March 1948. A few months shy of her 22nd birthday, Marilyn was eleven years his junior. They met at Columbia Pictures, where Fred was her vocal coach on the low-budget musical, Ladies of the Chorus. Later that year, he composed a song, ‘How Wrong Can I Be?‘, and asked Marilyn to sing on the demo. (Interestingly, the writer’s credit was initially attributed to ‘Terry Meredith,’ a composite of his daughter’s first and middle names.) The recording was forgotten until the 1990s when the original acetate was auctioned at Sotheby’s, and it can be heard in a scene from the Oscar-winning film, The Shape of Water (2017.)

In 1948, Terry and her father were living in her grandmother’s large home on Harper Avenue, West Hollywood, with her aunt Mary and cousins Ben and Anne. After their first date, Fred drove Marilyn home to a grimy apartment in a bad neighbourhood. He then invited her to his home, where she stayed for three weeks and grew close to his family, including Terry – until Fred discovered that Marilyn was actually a resident of the Hollywood Studio Club, a hostel for aspiring actresses.

Marilyn had made a similar claim to actor John Carroll in 1947, when she actually was living in a perilous situation. (An intruder had climbed through the window of her apartment on South Avon Street in Burbank while she was sleeping.) She stayed with Carroll and his wife, MGM talent scout Lucille Ryman, for a while until they arranged for her to move into the Studio Club.

Fred forgave this deception, but never fully trusted her again. And although Terry adored Marilyn, Fred said she was not ready to be a wife and mother. “He genuinely cared for her,” Terry says, “but her lie may have persuaded him that he shouldn’t marry her.” Early in their relationship, Fred arranged for Dr. Walter Taylor, a cosmetic orthodontist, to fit Marilyn with a retainer to correct the slight protrusion on her front teeth. Taylor treated her for free as a favour to Fred.

In August 1948, Fred’s divorce from Terry’s mother, Patti Sacks Karger, was finalised. Then in September, Marilyn’s six-month contract at Columbia lapsed. It’s thought she was dropped after spurning the advances of studio boss Harry Cohn. She had also suffered the loss of Ana Lower, with whom she had lived as a teenager, just days before meeting the Kargers. A former vaudeville artiste and wealthy widow of filmmaker Maxwell Karger, Ann (or ‘Nana,’ as everyone called her), soon took Ana Lower’s place as a mother figure to Marilyn.

Another key relationship was formed during Marilyn’s brief tenure at Columbia, with Natasha Lytess, who became her personal acting coach for the next six years. Marilyn spent a lot of time at her home on North Harper Avenue, which was conveniently close to the Kargers. Terry’s mother Patti, a former showgirl and actress, was studying for a law degree. She graduated in 1952, and would become a prominent Hollywood attorney. Marilyn would spend that Christmas with the Kargers, buying extra gifts for Mary’s children when she noticed their stack under the tree was smaller than Terry’s. Patti was also there, apparently accepting Marilyn as part of their extended family.

That December, columnist Louella Parsons had reported that producer Lester Cowan was putting her on contract. She had recently filmed a walk-on part in the final Marx Brothers movie, Love Happy. After Cowan confirmed the news to Marilyn, she rushed to a jeweller with the Los Angeles Examiner clipping and persuaded him to let her buy a $500 gold watch on an instalment plan. She gave the watch to Fred that Christmas, but decided not to engrave it, explaining that she knew he’d find another girl, and he wouldn’t be able to wear the watch if her name was on it. The Cowan contract amounted to little more than an East Coast publicity tour, which she left after Cowan allegedly made a pass at her.

Although Fred Karger was not formally identified in Marilyn’s 1954 memoir, My Story, her account of their relationship spanned three chapters. As she struggled to overcome stage fright, he encouraged her to sing for party guests and accompanied her on the piano. She gradually learned to mask her insecurities in company, but was secretly hurt when he criticised her shortcomings.

Terry dispels the rumour that family members including Ann Karger begged him to make Marilyn his wife. Though he would always care for her, Fred was looking for a more mature, less demanding woman. Despite their mutual attraction, he was also uncomfortable with Marilyn’s sexy appearance and hunger for fame. He was frequently too busy to see her, and she stayed at home for hours, waiting for his call.

Terry says the relationship lasted until spring of 1949, but most biographers estimate they had parted back in the autumn of 1948. Fred escorted Marilyn to a New Year’s Eve party at the home of producer Sam Spiegel. It is thought she met her next lover, 53-year-old Johnny Hyde, that night. A top-ranking talent agent, Hyde would help to secure her breakout roles in The Asphalt Jungle and All About Eve, and a permanent contract at Twentieth Century-Fox. The age gap was considerable, however, and although Hyde left his wife and children for her, she spurned his offers of marriage.

In February 1949, Marilyn and the Kargers saw Ladies of the Chorus at the Carmel Theatre on Santa Monica Boulevard. She was thrilled to see her name on a marquee for the first time. Outside the theatre, Mary marvelled that nobody recognised her. “In the movie, I’m Marilyn Monroe,” she replied. “Out here, I’m Norma Jeane.” This was an early instance of her uncanny perception that ‘Marilyn Monroe’ was a mirage she could turn off and on at will.

She doted on the Karger children, and often took Terry (whom she nicknamed ‘T.K.’) to Wil Wright’s Ice-Cream Parlour after school. A few days before her seventh birthday, Terry noticed a beautiful blue dress in a shop window. Marilyn surprised her with the dress at her birthday party, a gesture Terry would appreciate even more when she realised that Marilyn had little money to spare. Marilyn also once pranked guests at a house party, promising to introduce them to “my guard dog – Fang.” All the children of the Kargers’ extended family – including Terry’s cousins, Johnny and Jacqui Warren – loved playing with Josefa, Marilyn’s short-haired Chihuahua, given to her by movie mogul Joe Schenck. (Natasha Lytess was less fond of Josefa, who was never fully house-trained.)

Even after their breakup, Fred continued taking Marilyn out for dinner at clubs on the Sunset Strip, and they once took a road-trip to Virginia City, the Old West town near Lake Tahoe, Nevada. Terry often joined them on drives to beaches in Santa Monica and Malibu, and further ventures to the botanical garden and mission at Santa Barbara, and Anza-Borrego in the Colorado Desert of California. In 1950, Marilyn sang for the Marine Corps at Air Station El Toro near Irvine, California. Fred joined her for moral support, and was impressed by her performance.

“I really loved her,” Terry says, “which is why, to this day, I miss her deeply. I would have been thrilled to have had her as my stepmother, but Daddy knew his own heart, his own mind, and had his own reasons … After they’d been together for a while, I really thought Daddy and Maril would get married. I certainly wanted them to; when it didn’t happen, I couldn’t understand why.” Marilyn regularly had dinner with the Kargers, helping Nana in the kitchen and having “heart-to-heart talks.” Nana also sometimes mended her clothes, and Marilyn sent her birthday gifts and cards, and a dozen red roses on Mother’s Day.

By 1952 Marilyn was on the cusp of stardom, and Johnny Warren remembers how her role in Niagara “changed everything.” Reporters showed up at the Kargers’ door, only to be fobbed off with “Marilyn who?” It was also an exciting year for Freddie, who wrote the score for From Here to Eternity, starring his friend Frank Sinatra. But although the score earned an Oscar nomination, the credit went to Columbia’s musical director, Morris Stoloff.

Marilyn was now dating Joe DiMaggio, and Fred would marry Jane Wyman in November. Terry debunks the story that Marilyn gatecrashed their wedding reception at Chasen’s restaurant in Los Angeles, as reported by columnist Sidney Skolsky. In fact, Fred and Jane were married in Santa Barbara, and he and Terry moved into her Beverly Glen home soon after.

In her next film, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Marilyn proved her own musical talents to the world, and would perform ‘Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend’ at Jane’s birthday party, and at subsequent family gatherings – accompanied by Fred on piano. Johnny Warren often made recordings on these Sunday nights, but sadly the tapes are lost. “She wouldn’t just sing it – she had it choreographed and would strut it,” he recalled. Another favourite song was ‘Do It Again.’ Marilyn gave Terry a 16 mm movie projector, which she passed on to Johnny. She offered make-up tips to Terry (now eleven), and advice about her parents’ divorce and Fred’s remarriage, once gently admonishing Terry when she was rude to her father.

In September 1953, the Kargers watched Marilyn’s appearance in a skit for The Jack Benny Show on television. She was now living at North Doheny Drive, where Jacqui Warren – now a student at UCLA – would often drop by. Soon after her engagement to DiMaggio was announced, she was mobbed at an airport. One of his bodyguards rescued her, and took a shaken Marilyn to Nana’s house.

They married in January 1954, while Marilyn was on suspension after refusing a script from Twentieth Century-Fox. The stalemate was broken when Joe Schenck, the studio’s co-founder, urged legendary songwriter Irving Berlin to recommend Marilyn for There’s No Business Like Show Business; and when taking the part, Marilyn was guaranteed that her next picture (The Seven Year Itch) would be her own first choice.

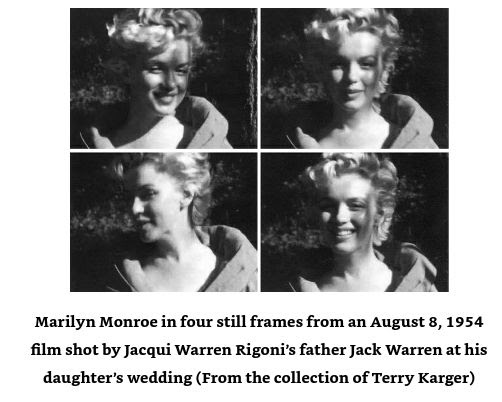

On August 8, 1954, 18-year-old Jacqui Warren married Herb Rigoni at a Catholic church in Encino. Marilyn wanted to slip in unnoticed, so while Fred and Jane sat in the front of the church, she snuck up the stairs to the choir loft at the back of the building with Nana and Terry. Unfortunately, her cover was blown when she tried to slip out after the ceremony, bumping into a startled Fred and Jane outside the church, and she was also briefly spotted in a family home movie. (She would revisit the church in 1961 for the baptism of John Clark Gable.)

After just nine months of marriage, Marilyn and Joe separated. “The only time I saw Marilyn angry was in the days before the divorce,” Terry says. “She used Nana’s phone to call him, and I can remember how her enraged face and loud voice made me frightened for her.” Finally, she set the receiver in its cradle as Joe was talking – and he didn’t call back. Only two months later, Fred and Jane also separated. He went on to date another blonde beauty, Kim Novak, whom he worked with at Columbia.

By this time, Mary’s husband, Major Walter Short, had been transferred to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Nana sold her house on Harper Avenue and moved to the Voltaire Apartments (now known as Granville Towers) on North Crescent Heights. After leaving Joe, Marilyn quietly moved in with Nana and finished shooting The Seven Year Itch. She didn’t even tell the studio her new address, as she was making plans to abandon her restrictive contract and set up an independent production company with photographer Milton Greene.

She flew to New York with Mary that December and began her new life. But she would be reunited with the Kargers a few months later, when she gave them front-row tickets to a charity circus at Madison Square Garden, and made her grand entrance in true showgirl style, riding a pink elephant. The Kargers sat near Joe, with whom she was now on better terms. Joe grew closer to the Kargers after his separation from Marilyn. He once visited Nana’s home and shared his regret at losing Marilyn, in front of her brother John and a rather uncomfortable Freddie. Joe also befriended Mary during his frequent trips to the East Coast, and they became golfing buddies.

Marilyn’s nickname for Mary was ‘Buddynuts,’ and along with Patti, the women liked to play jokes, and were known as the ‘Devilish Trio.’ When Patti was dating electronics executive Howard Thomas, she covered a giggling Marilyn in wrapping paper and brought her to Howard’s door on his birthday. And on another occasion, Mary and Patti were passengers in Marilyn’s car when Frank Sinatra and Peter Lawford drove by in the opposite direction. They shouted out to Marilyn, who yelled back, “Bye guys!” and swiftly floored the accelerator. Sinatra turned around and gave chase, but was no match for Marilyn driving at top speed. “I’ve had plenty of experience being chased by photographers,” she told Patti.

A further story of the Devilish Trio has the Devilish Trio stealing a lifesize cutout of Marilyn in her famous ‘skirt-blowing’ pose from Grauman’s Chinese Theatre after The Seven Year Itch opened in June 1955, and placing it on Jane Wyman’s front lawn. Terry says that Marilyn was promoting the film in Los Angeles, but other accounts place her in New York at the time, so she may not have been personally involved.

In the summer of 1955, Fred spent time in New York, working on The Eddy Duchin Story, a biopic of the popular bandleader who died at 42. Some scenes were filmed at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, where Marilyn was then living. Recalling that she was a fan of leading man Tyrone Power, Fred invited her to a cast party at the hotel. However, when he called her from the front desk, she said she wasn’t ready. She called him back two hours later, but by then she was groggy with drink (or pills), and a disapproving Fred told her to sleep it off instead.

When he first knew Marilyn, she kept a strict diet, exercised regularly, and avoided stimulants (even coffee), in line with Ana Lower’s Christian Science teachings. Over the years, however, she had developed a taste for champagne, and increasingly turned to sleeping pills to relieve insomnia and stress. “Though Daddy was frustrated about Marilyn not accompanying him to the party,” Terry says, “he didn’t understand her emotional turmoil or know about the powerful meds she was taking to deaden her pain.”

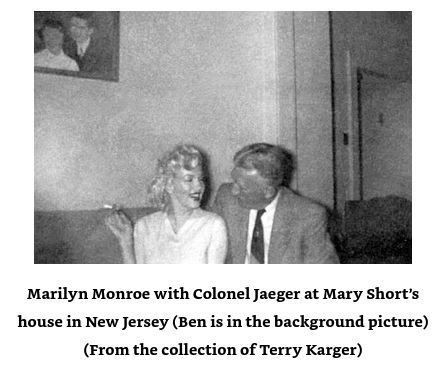

Marilyn also visited Mary in New Jersey. She was now taking classes at the Actors Studio in New York, and offered to sponsor Mary’s son Ben, who was interested in acting. However, Mary’s husband refused the offer, which Ben would only discover years later. In 2009, a grainy video of Marilyn sharing a cigarette with Mary was circulated online, leading to speculation that they were smoking marijuana. Gretchen Ann Reid, a friend of Mary’s daughter Anne, had acquired a VHS copy shortly before her death in 1997. It was later sold at auction for $275,000, with Gretchen claiming to have shot the footage herself. (Gretchen also claimed that she and Anne had a sleepover at Marilyn’s Los Angeles home shortly before her death in 1962, but Anne was working as a showgirl in Reno at the time.)

Actually, the footage was filmed by Mary’s husband Walter, a US Army captain. Anne’s closest friend at the time was not Gretchen, but Carolyn Bell, daughter of a general. As Ben says, for members of a military family to be caught using drugs could have landed these men in a military prison. Furthermore, it seems very unlikely that Marilyn would have permitted them to film her smoking marijuana. (At Jacqui Warren’s wedding the previous year, she had been concerned that even speaking on camera could be construed as a violation of her Fox contract.)

Anne can also be seen in the heavily edited online video, which bears little resemblance to the original home movie, shot in 16 mm Kodachrome. Ben’s girlfriend Dee Maddox, Colonel Charles ‘Chuck’ Robertson and his wife Betty were also present that day, as well as another man, Colonel Jaeger, and Ben’s friend Alan. Several snapshots are featured in the book. Terry dates this event to 1956, but it is more likely to have occurred during the previous spring or summer. Ben also claims that Marilyn visited again in 1959, when a neighbour spotted her and called out the Fire Brigade. She spent most of the afternoon signing autographs for firemen.

In March 1956, Marilyn returned to Los Angeles to shoot Bus Stop, but she was back in New York by June, when she married Arthur Miller. She then travelled to London in July to film The Prince and the Showgirl. Terry says that Marilyn flew to Los Angeles on a break from filming, and confided in Nana her nerves about meeting Elizabeth II at a Royal Command film performance in October. However, Michelle Morgan’s recent book, When Marilyn Met the Queen – which covered the four-month shoot in detail – indicates that she remained in England throughout. Perhaps Ann Karger spoke to her on the telephone. According to Terry, she advised Marilyn to “look her straight in the eye and say to yourself, ‘I’m just as pretty as you are.’”

Marilyn spent the next 19 months living quietly with husband Arthur between their homes in New York and Connecticut. While spending the summer of 1957 at a summer house in the Hamptons, she developed a life-threatening ectopic pregnancy which had to be terminated, bringing a happy period of her life to an abrupt end. Then in July 1958, she returned to Hollywood to make Some Like It Hot, and was reunited with Terry while visiting Nana’s home. When Terry told her she wanted to become a teacher, Marilyn was delighted. “I can’t think of a more important job in the world,” she said. “Children need teachers they can look up to. Just be the person you were meant to be, T.K. Looks will get you far, but not as far as a good education.”

Marilyn became pregnant again during the shoot, but would miscarry after returning to New York. She called on December 16 to share the sad news, leaving Nana in tears. In September 1959 she flew to Los Angeles briefly to meet Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, and then returned in early 1960 to film Let’s Make Love. She began work on The Misfits in Nevada immediately afterwards, and by November, she and Arthur Miller were separated.

In July 1960, Fred had been invited to perform with his orchestra at the Democratic Convention in Los Angeles. Terry says he had heard rumours that Marilyn was involved with presidential nominee John F. Kennedy and his brother, Bobby Kennedy – who would be appointed as Attorney General when the elder Kennedy entered the White House in January 1961 – and refused to go. However, Marilyn did not attend the event (she was in New York at the time, doing wardrobe tests for The Misfits.) After her death, Marilyn’s association with the political dynasty became the stuff of legend, but the most reliable sources place their earliest acquaintance in the winter of 1961/62.

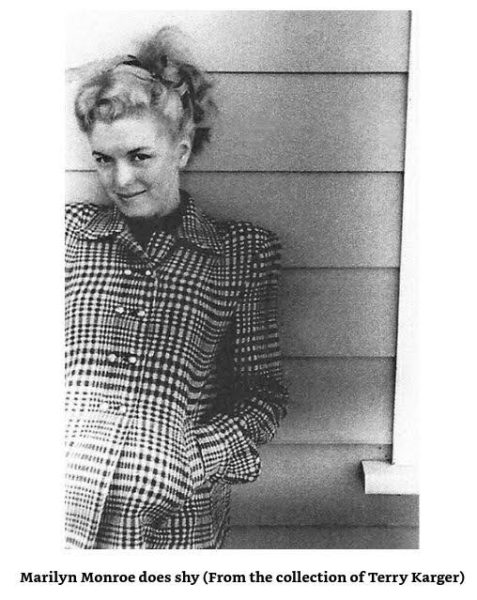

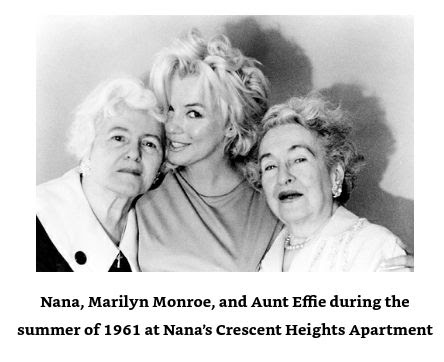

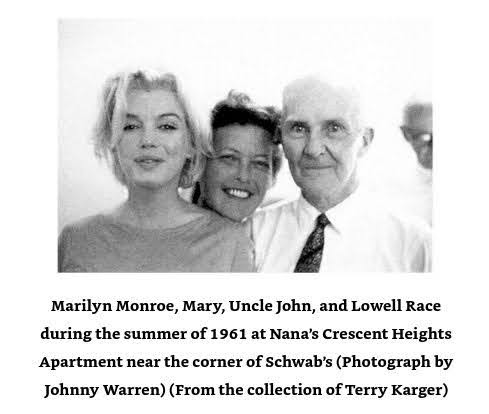

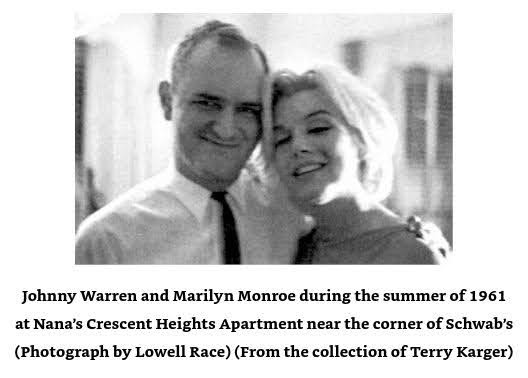

Marilyn returned to Los Angeles on a semi-permanent basis in July 1961. Terry’s cousin Johnny saw Marilyn for the last time at Nana’s apartment that summer, and he took several family photos on that day. “I recall changes in Marilyn after she’d been working with Lee Strasberg,” he says. “Her poise was different – her facial expressions and the way she spoke. She became more refined and focused on what she could do to improve her acting, to communicate her thoughts … But deep down, she was very shy. She’d had a hard childhood and she needed a family, someone to love and to love her … I don’t think she ever really understood her fame. She knew her fame was there, but she was too genuine somehow, and that didn’t quite work in Hollywood.”

Terry was about to begin her junior year at the University of Southern California when Marilyn invited her to lunch at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Her hair was in pigtails and she had lost weight following gallbladder surgery. They didn’t discuss her divorce from Arthur Miller, but Marilyn mentioned Joe DiMaggio. “Joe and I aren’t getting back together,” she said, “but we’re better friends now than when we were married.”

They also talked about Fred Karger’s remarriage to Jane Wyman in March 1961. “Do you think they’re happy together?” Marilyn asked. “I really want Freddie to be happy,” she added, then laughed wistfully and looked away. “Oh, why did Jane get to marry Freddie twice and I never got to marry him once?”

Marilyn moved to another apartment on North Doheny Drive that September, and Terry visited her there. She was introduced to Maf, Marilyn’s latest pet dog, whom she said was a gift from Frank Sinatra. (Terry describes seeing a white piano in the room, but she may be remembering Marilyn’s previous Doheny address, as the piano had been moved to her New York apartment several years before.) “Maril was happy, I was happy, and there was no reason to suppose this might be the last time we’d meet,” Terry says. “It saddens me that I can only remember impressions: her hug, her kiss on my cheek, the joy in her eyes … Had I known how soon I would lose her, I would have tried to capture every moment and remember every word.”

“Although she asked me about school and our family, we didn’t talk about her secret affair with President Kennedy,” Terry admits. “Yet while she was alive, Mom and Nana didn’t mention what they knew about her affairs with the Kennedy brothers. It was only after her passing that they said something to me and my family.” Patti had liaised with the Attorney General while investigating mortgage fraud in 1960, and Terry was among the crowd that gathered around the President following his address to USC students in the days before his electoral victory. She also recalls watching Marilyn’s performance of ‘Happy Birthday Mr. President’ at Madison Square Garden on television in May 1962.

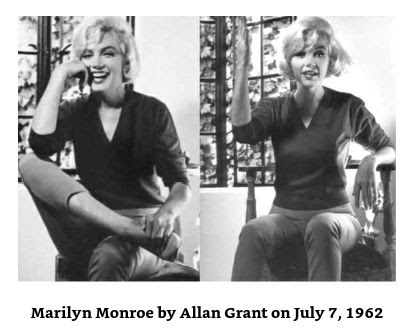

When footage from Marilyn’s unfinished last film, Something’s Got to Give, was released many years later, Terry thought she was “at the pinnacle of her beauty.” But while viewing test shots, Terry sensed that “despite being photographed her entire adult life, she was still not comfortable doing it. I could see all her insecurities coming out.”

In July, Marilyn called Mary’s daughter Anne, and asked her to come over to her grandmother’s apartment. “That afternoon, Nana and Marilyn talked for quite a while,” recalls Anne’s husband, Cherrill Consoll. “Marilyn had brought her dog Maf and arrived with her chauffeur Rudy [Kautsky.]” Marilyn wanted Mary – who had also returned to Los Angeles – to be her manager, but she didn’t think it was a good idea. “I walked away with the impression that Marilyn was a very troubled woman,” Cherrill reflects. “After all the talk, Marilyn started to play the piano while Nana and Mary were singing songs.”

On Friday, August 3, Marilyn spoke on the phone with Nana and they discussed her recent interview for Life magazine, which hit newsstands that day. Nana said she sounded “Happy, even excited” during their last conversation, like “a giddy teenager in love … Maril insisted she knew what she was doing.” In Nana’s opinion, she did not sound like a woman on the brink of suicide. However, others who knew Marilyn at this time have confirmed that her moods could change in an instant, and whether by accident or design, she had overdosed many times before. “Maybe she’s happier where she is,” Johnny Warren says. “The world today would probably be very cruel to her.”

“After Maril passed away, Nana and Mom each told me about conversations they had with her, which convinced me that Maril had affairs with two of the Kennedy brothers,” Terry says. “Nana was terrified for Maril, fearing she was in way over her head.” Nana’s brother, John Conley, had been a friend of Joseph Kennedy, the family patriarch. “The father of the Kennedy brothers had been relentless in pursuing and maintaining power,” Terry says. “Would his sons be any different?”

On Sunday, August 5, Terry learned of Marilyn’s death while listening to a radio news bulletin. Joe DiMaggio flew from San Francisco to claim her body and arrange the funeral. Nana, who “cried for weeks,” attended the small ceremony with Mary, and can be seen at Joe’s left in one press photo. “If only she had lived long enough to absorb more of Nana’s motherly wisdom,” Terry says. “Maril was a paradox; one of the strongest people I’ve ever known and also one of the most fragile … Daddy grieved Maril’s death very deeply.”

The book also contains a chapter exploring the conspiracy theories relating to her death, with all the usual tropes: Marilyn was planning to hold a press conference and tell all about her affairs with the Kennedys (highly unlikely, as it would have damaged her reputation more than theirs); a ‘diary of secrets’ (never found, and judging by her infrequent writing habits, it probably didn’t exist); and the bizarre stories of an ambulance taking her alive, only to return to her home in Brentwood when she died on the way to the hospital. As with ghostwriter Jay Margolis’ 2014 book, The Murder of Marilyn Monroe: Case Closed, this chapter combines numerous threads of speculation, and claims that she could not have ingested such a large dosage orally. In fact, her tolerance for barbiturates was dangerously high, which is not uncommon among long-term prescription drug addicts.

In October 1963, Jane Wyman left Fred Karger for good. “Jane and I love each other very much, but we can’t live together,” he told Terry. Their friendship endured, however. Terry took a teaching job at Crescent Heights Elementary School. She continued teaching for 28 years, and has also travelled widely. “I enjoyed teaching very much,” she says, “but I sometimes wonder what it would have been like to attend the USC School of Cinema. I would not have wanted to act, because of my certain shyness, but I would’ve liked to have been involved in some way in the motion picture business. I guess it ‘runs in the family,’ but Daddy never encouraged it.” Fred Karger died exactly seventeen years after Marilyn, on August 5, 1979, with his friend Jack Lemmon – Marilyn’s co-star in Some Like It Hot – delivering the eulogy at his funeral. Screen goddess Rita Hayworth, with whom Fred had worked at Columbia, was also present.

“I ran the camera department at Fox for about fourteen years,” Johnny Warren says. “The custodians and drivers all spoke highly of Marilyn. I’ll never forget that. And I never once told them I knew her. The working people were really sorry she wasn’t there anymore. They said, ‘Oh, she was so sweet. She treated us like real people.’ Here’s this dear girl that we loved. I was right there years after she had passed on, but her existence was still very much felt.”

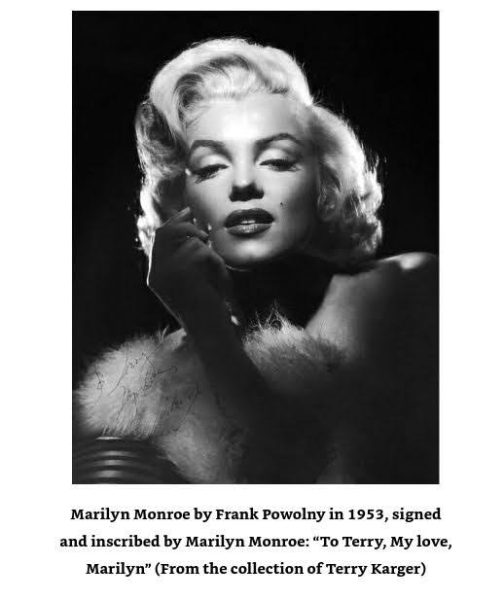

My Maril sheds new light upon Marilyn’s enduring friendship with the Karger family, a little-known aspect of her life. Terry’s memories are touching, if sometimes a little naïve, as one might expect of a relationship formed in early childhood. Marilyn had a habit of ‘compartmentalising’ her circle of friends, leading each to believe they were her most intimate confidante. She was more volatile than Terry ever knew; yet she was also a loving and generous friend to those she cared about, and children most of all. The book also includes several rare photos, a welcome addition though the reproduction quality leaves something to be desired.

The narrative becomes rather patchy following her move to Manhattan, with hefty chunks of biographical material padding out what could have been a leaner, more concise volume. Lengthy interviews with actors Jane Russell, Robert Mitchum, and Don Murray, as well as photographer Len Steckler and journalist Richard Meryman, are quite enjoyable; but for readers familiar with Marilyn’s story, they won’t break new ground. These segments are attributed to Jay Margolis, possibly in collaboration with his former writing partner, Richard Buskin (author of the excellent 2002 book, Blonde Heat: The Sizzling Screen Career of Marilyn Monroe.)

Of course, the later chapters fall under the shadow of well-worn conjecture; and as with other Monroe memoirs, its chief eyewitness is not a detached observer. As time passes, however, direct accounts like My Maril – drawn from living memory – are rapidly diminishing. Terry Karger’s voice deserves to be heard; and Maril: Marilyn Monroe, Ronald Reagan, Hollywood, and Me will reward those seeking a more personal view with dazzling glimpses of an unassuming California girl who conquered the world.

You must be logged in to post a comment.