Tags

Arthur Miller, BFI, British Film Institute, Clark Gable, John Huston, Marilyn Monroe, Montgomery Clift, The Misfits

The Misfits (1961) was reissued in the UK and Ireland in June, and also headlined a major retrospective, ‘Marilyn’, at the British Film Institute on London’s Southbank. The month-long season featured all but one of the sixteen films Marilyn Monroe made from 1952-62, of which The Misfits would be her last. Her leading man, Clark Gable, suffered a fatal heart attack days after filming ended, while Monroe – who battled insomnia, drug addiction, and the collapse of her marriage during the shoot – never completed another movie.

The Misfits (1961) was reissued in the UK and Ireland in June, and also headlined a major retrospective, ‘Marilyn’, at the British Film Institute on London’s Southbank. The month-long season featured all but one of the sixteen films Marilyn Monroe made from 1952-62, of which The Misfits would be her last. Her leading man, Clark Gable, suffered a fatal heart attack days after filming ended, while Monroe – who battled insomnia, drug addiction, and the collapse of her marriage during the shoot – never completed another movie.

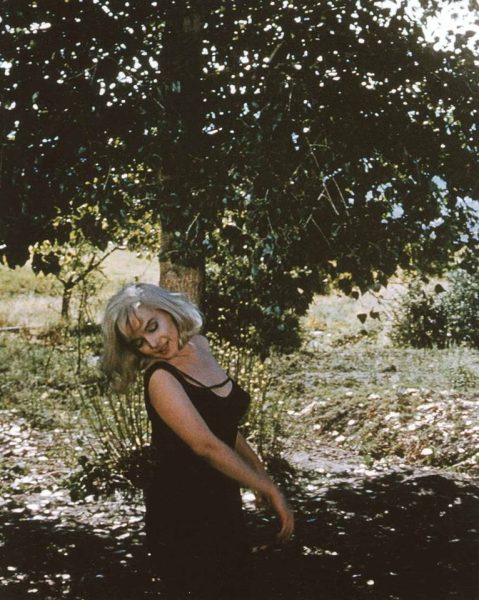

Marilyn’s posthumous celebrity is unsurpassed, yet many of her fans will never see her on the big screen – although in her lifetime, she transfixed cinema audiences. Watching her as divorcee Roslyn Tabor, dancing with Guido (Eli Wallach) in his abandoned desert hut, one is reminded of Monroe’s potent physicality. Several drinks later, she wanders outside and hugs a tree. Even if unsteady on her feet, she exudes balletic grace.

Photo by Inge Morath

The screenplay, by husband Arthur Miller, draws on Marilyn’s biography in particular. Did she really want to expose her mother’s neglect, and her own childlessness, in this performance? Her subsequent rejection of Miller suggests not. In one scene, Guido peeks at pin-up shots in her closet. The film seeks to condemn her sexual objectification, but is also innately voyeuristic.

A disturbing bar scene, in which drunken cowboys slap the behind of an unwitting Roslyn while she plays paddleball, is even more jarring as cameraman Russell Metty had previously shot a gratuitous close-up of her rear during a horse-riding sequence. Nonetheless, director John Huston refused Marilyn’s request to show her bare breast in a bedroom scene, bowing down to the censors of an era when innuendo was rife but actual nudity was taboo.

Befitting Miller’s theatrical background, The Misfits is essentially a three-act drama – and by its midpoint, with the exit of her friend Isobel (Thelma Ritter), Monroe is left alone among the men, while the semi-lunar bleakness of the Nevada landscape is intensified by Metty’s monochrome cinematography. The interior scenes verge on claustrophobic, as if the viewer is in the same room, in real time, witnessing the disintegration of the narrative (and the characters themselves.)

As Perce Howland (Montgomery Clift) enters, the real-life accident that deformed his visage several years before is referenced into his character’s backstory. He later falls off his horse at a rodeo, and a bandaged head completes this portrait of a wounded soul. Later, outside a bar, he rests his head on Monroe’s lap. Surrounded by wrecked cars and garbage, she tries to comfort him.

Photo by Eve Arnold

Although Marilyn idolised Gable, her empathy with Clift makes this dialogue a highlight of The Misfits, and one of the outstanding scenes of her career. Clift, burdened by alcoholism and the strain of hiding his bisexuality, would make three more films – including Freud, another fraught epic with Huston – before his death in 1966.

After they return to the hut where Roslyn now lives with Gay Langland (Gable), she finds herself having to ‘mother’ all three cowboys, whose display of drunkenness is utterly convincing. As her rural idyll falls apart, she reluctantly joins the men on their mission to round up wild horses in the hills. But when she learns that the horses are to be slaughtered for dogfood, Roslyn tries to stop the men – leading to a bitter confrontation with Gay.

These harrowing scenes benefit most from the panoramic view of the big screen. The pursuit and capture of the horses only intensifies the desperation of their hunters. Filmed from a distance, Roslyn screams at the men. She appears hysterical to them, but today’s filmgoers may share her horror when confronted by the realism of the chase.

By contrast, the final frames – with Gay and Roslyn driving away in the dark – seem to signal a neat Hollywood ending, providing tentative hope in a film plagued by existential doubt.

Miller and Huston seemed unable to conceive of Roslyn making it on her own. But behind the scenes, Monroe would soon divorce Miller – and before long, the sexual revolution and feminist surge would transform relationships between men and women. Roslyn’s affinity with animals and nature now seem less like the irrational fears of a neurotic woman, than a glimpse into our dystopian present when ecological disaster is becoming a reality.

But this was an era that Gable, Monroe and Clift would never know. Critics were bemused by the film, and it opened to a muted reception. Even now, The Misfits wields an unsettling power. When Guido tells Roslyn, “Here’s to your life. I hope it lasts forever”, there was an audible gasp from the stalls. This ironic nod to mortality might be too much to bear.

Thank you for the insightful perspective on The Misfits which would set the stage for the tragic last year and a half of Marilyn Monroe’s life: her admission into the Payne-Whitney Psychiatric Clinic, reuniting with Joe DiMaggio, an affair with JFK, the infamous weekend at the gangster hangout Cal Neva, the ill-fated “Something’s Got to Give”, and ultimately her death.

Pingback: ‘The Misfits’ at the BFI | ES Updates