Tags

2025, A Year in Books, Alba de Céspedes, Allegra Goodman, Andrew Miller, Another Man in the Street, Barbara Windsor, British Blonde, Carol White, Caroline Fraser, Caryl Phillips, Celia Dale, Crime Fiction, Crooked Cross, Daniel Kehlmann, Darryl W. Bullock, Diana Dors, Emma Donoghue, Eric Tucker, Ethel Carnie Holdsworth, G.W. Pabst, Gabriele Tergit, Germany, Havoc, Isola, Italy, Joe Meek, Julie Christie, Louise Brooks, Love and Fury, Lynda Nead, Murderland, Noah Eaton, Other People, Pauline Boty, Rebecca Wait, Rickard Sisters, Ruth Ellis, Saint of the Narrows Street, Sally Carson, Shadow Ticket, The Director, The Effingers, The Harrow, The Land in Winter, The Paris Express, The Secret Painter, There's No Turning Back, This Slavery, Thomas Pynchon, William Boyle

I read Thomas Pynchon’s first novel, The Crying of Lot 49, for my American Literature module at university – and like most of the books I studied back then, I haven’t returned to it in thirty years. But after seeing Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice, I started thinking maybe Pynchon wasn’t just another of those great white males I generally avoid like the plague. And that I might even enjoy reading one of his books, if the same kind of mayhem conjured on the screen could also be found within its pages.

In what has been a good year for fiction (if not our lived experience), Shadow Ticket was my most anticipated read of 2025. Pynchon’s first novel in twelve years was published shortly after Anderson’s second adaptation of his work, One Battle After Another, opened last autumn. Set during the last days of Prohibition – with the Great Depression in full swing, and storms brewing over the Atlantic – Shadow Ticket‘s blurb also promised screwball antics with a cast of two-bit detectives, hardboiled dames and a runaway heiress to boot, all set to a Jazz Age tune.

With the world apparently now stuck on a zombie 1930s cycle (minus the Art Deco), this was the only vibe shift I wanted. Pynchon careens through an ever-changing cast of characters and locales, from Milwaukee to Budapest; and while Shadow Ticket may be patchy, nobody else wrote as brilliantly this year.

Daughter of a Cuban diplomat, Alba de Céspedes became one of Italy’s leading writers at an inauspicious moment. First published in 1938, There’s No Turning Back faced immediate censure from Mussolini’s regime. This expansive novel follows a group of young women in their final year of study, relishing life in the city as they face an uncertain future. In contrast to the simmering family drama of 1952’s Forbidden Notebook, its youthful vitality reflects the author’s formidable range. re-empting Mary McCarthy’s The Group by 25 years, There’s No Turning Back is translated by Ann Goldstein, who also brought Elena Ferrante to English-speaking readers. Alongside Elsa Morante and Anna Maria Ortese, Alba de Céspedes joins a pantheon of Italian women writers who helped to make Ferrante’s career possible.

Daughter of a Cuban diplomat, Alba de Céspedes became one of Italy’s leading writers at an inauspicious moment. First published in 1938, There’s No Turning Back faced immediate censure from Mussolini’s regime. This expansive novel follows a group of young women in their final year of study, relishing life in the city as they face an uncertain future. In contrast to the simmering family drama of 1952’s Forbidden Notebook, its youthful vitality reflects the author’s formidable range. re-empting Mary McCarthy’s The Group by 25 years, There’s No Turning Back is translated by Ann Goldstein, who also brought Elena Ferrante to English-speaking readers. Alongside Elsa Morante and Anna Maria Ortese, Alba de Céspedes joins a pantheon of Italian women writers who helped to make Ferrante’s career possible.

Andrew Miller’s Booker finalist, The Land in Winter, follows two young married couples living in England’s west country during the big freeze of 1963. An ambitious doctor neglects his trophy wife; while their neighbours, a novice farmer and his flighty spouse, are ill-prepared for family life. Although bleak in parts, the novel is tempered with good humour, as a new generation strives for change while engulfed by the eternal. (You can read more about modern Britain’s crossroads period in David Kynaston’s On the Cusp: Days of ’62, Tessa Hadley’s The Party; and my own novella, Wicked Baby.)

I enjoyed Rebecca Wait’s debut, The Followers, back in 2015, and had wondered whatever happened to her – until now, that is. Havoc is her fifth novel, so she’s obviously been doing just fine on her own. Set in a run-down girls’ boarding school on the South Coast during the nuclear panic of the mid-1980s – all times and places with personal resonance for me – this appropriately named tale (think St. Trinian’s meets Muriel Spark) is the funniest I’ve read this year.

Sally Carson, an English author of the interwar period, spent youthful summers with friends in Bavaria before writing her remarkably prescient first novel. Published in 1934, Crooked Cross traces the Nazis’ rise to power through the prism of a large, loving family in a German mountain village, with the doomed romance at its heart showing how racial hatred could tear apart the most peaceable communities. Carson went on to write two further novels continuing the saga, but after her death in 1941, she was largely forgotten. Almost 90 years out of print, Carson’s The Prisoner will also be reissued in April 2026.

Daniel Kehlmann’s The Director looks back at the Nazi regime from a very different angle. G.W. Pabst was one of Weimar Germany’s leading filmmakers, perhaps best-known today for Pandora’s Box. After Hitler came to power, Pabst joined other artists leaving for America. But unlike his peers, Fritz Lang and Billy Wilder, Pabst didn’t thrive in Hollywood’s dream factory; and after a brief sojourn in occupied Paris, was fatally drawn back to Berlin. Under the dubious patronage of Joseph Goebbels, Pabst resumed his film career; but while he was never a propagandist like Leni Riefenstahl, his reputation soon faded. With cameo appearances from Louise Brooks and Greta Garbo, Kehlmann’s inventive, dynamic novel is one of the best cinematic fictions I’ve read.

In 16th century France, a nobleman’s orphaned daughter is raised under a relative’s remote guardianship. As she comes of age, her protector’s demands become ever more stifling, and as he orders her to join his mission to the New World, our heroine defies the man who holds her fortune in his hands. Faced with the ultimate punishment, she must fend for herself amid daunting odds. Inspired by the true story of Marguerite de La Rocque, Allegra Goodman’s Isola is a compelling yet ultimately hopeful study of one woman’s quest to escape coercive control, wrapped up in a rollicking adventure.

The midcentury English novelist, Celia Dale, wrote a number of psychological thrillers which have recently been reissued to considerable acclaim. First published in 1964, Other People focuses on June, a naive, self-centred teenager living with her mother in a seaside town, while her father recuperates abroad from a mysterious illness. After his sudden reappearance, the family move to the Bristol suburbs. Wilful and suspicious, June sets out to discover the truth about the stranger in their home, even as her sheltered life unravels.

In 1895, a boy boards a train to Paris. It will be his first journey alone, but the carriages are crowded, and as The Paris Express hurtles along, a race against time ensues. Inspired by a real-life derailment, Emma Donoghue’s thrilling novel embodies the hopes and fears of a people approaching modernity, with appearances from contemporary figures who may (or may not) have been among the passengers.

First published in 1951, Gabriele Tergit’s The Effingers is a sweeping saga, charting the evolution of Berlin from a mid-19th century backwater to grand metropolis and backdrop to modern Europe’s greatest tragedy. Two ambitious brothers open a munitions factory and marry into a banking dynasty, staking their claim as part of a fledgling Jewish elite. But as the next generation enters a world at war, resentment takes hold and their fortunes are reversed. Tergit wrote from personal experience, having fled Berlin after Hitler’s rise to power. Overlooked by postwar readers, her novel reads like a survivor’s testimony, and the street where she grew up now bears her name.

I also enjoyed Caryl Phillips’ Another Man in the Street, unpacking a Caribbean immigrant’s double life in Britain; William Boyle’s Saint of the Narrows Street, a New York story tracing the far-reaching consequences of one family’s hidden crime; and Noah Eaton’s The Harrow, set in the run-down office of a scurrilous London newspaper.

The Secret Painter, Joe Tucker’s memoir of his uncle, Eric Tucker, is an affectionate tribute to the fierce integrity of a self-taught, working-class artist; and Love and Fury, the final book from music historian Darryl W. Bullock, is a definitive account of Sixties pop producer Joe Meek’s maverick sound and shocking downfall.

With Heatwave, John L. Williams revisits Britain’s long hot summer of 1976, showing a daily buildup of social unrest amid shifting cultural trends; and Caroline Fraser’s Murderland ponders how the Pacific Northwest – America’s most polluted industrial region – experienced an unprecedented wave of serial killings during the Nixon years.

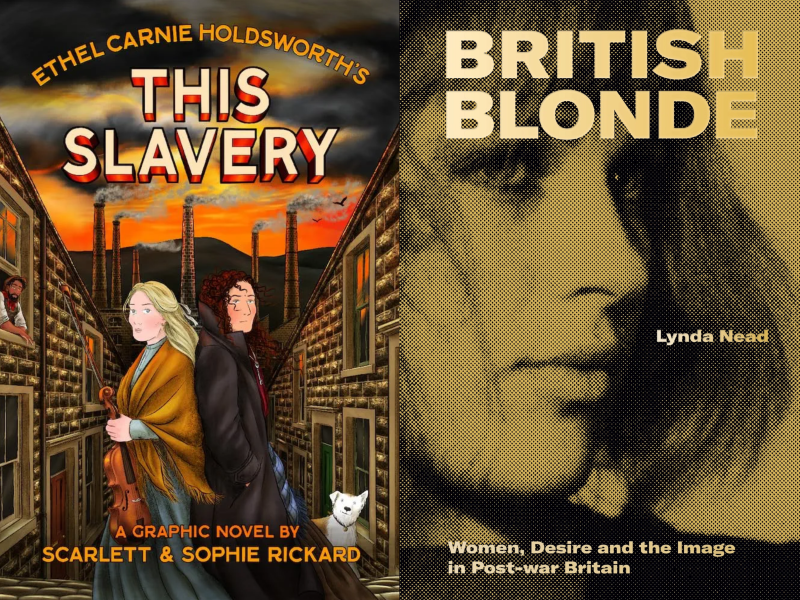

And finally, two arty tomes from my Christmas stocking: the Rickard Sisters’ adaptation of This Slavery, a 1925 novel by former mill-worker Ethel Carnie Holdsworth; and Lynda Nead’s meditation on a postwar phenomenon, British Blonde (from Diana Dors, Ruth Ellis and Barbara Windsor to Pauline Boty, Carol White, and Julie Christie.)

And finally, two arty tomes from my Christmas stocking: the Rickard Sisters’ adaptation of This Slavery, a 1925 novel by former mill-worker Ethel Carnie Holdsworth; and Lynda Nead’s meditation on a postwar phenomenon, British Blonde (from Diana Dors, Ruth Ellis and Barbara Windsor to Pauline Boty, Carol White, and Julie Christie.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.