Tags

42nd Street, A Ticket to Tomahawk, Alice Faye, Bernard F. Dick, Betty Grable, Broadway, Carousel, Darryl F. Zanuck, Down Boy, Fred Karger, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, George Cukor, How to Be Very Very Popular, How to Marry a Millionaire, Howard Hawks, Irving Berlin, Jane Russell, Jayne Mansfield, June Haver, Ladies of the Chorus, Let's Make Love, Marilyn Monroe, Mitzi Gaynor, Musicals, Orson Welles, Richard Zanuck, River of No Return, Sheree North, Shirley Temple, Something's Got To Give, Sonja Henie, The Girl Can't Help It, The Jazz Singer, There's No Business Like Show Business, Twentieth Century Fox, Vivian Blaine, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter

Bernard F. Dick, a professor of English and communication at Fairleigh-Dickson University in New Jersey, has published many titles on the classical era of Hollywood film-making, covering a wide range of figures like producers Harry Cohn and Hal B. Wallis; directors Joseph L. Mankiewicz and Billy Wilder; actresses Claudette Colbert and Rosalind Russell; and the blacklisted Hollywood Ten. In his 2018 book, That Was Entertainment, Dick hailed the MGM musical as the genre’s ‘Gold Standard,’ reeling off a list of the studio’s all-time greats from The Wizard of Oz to Singin’ in the Rain.

During the 1930s and ‘40s, ‘women’s pictures’ – which feminist critic Molly Haskell has broadly defined as a film with a woman at its centre – were at their zenith, but even MGM’s most acclaimed musicals, like Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) were driven by male protagonists, while Fred Astaire’s dancing partners were always the objects of his desire. Over at Twentieth Century-Fox (TCF), Darryl F. Zanuck helmed a string of hit musicals spanning three decades, having pioneered the story-based musical from the earliest days of sound.

However, the TCF musical was, as Dick writes, “a different type of women’s film: generally, a woman sets the plot in motion, controls it, or resolves it … because Zanuck had stars who were often playing versions of themselves … he selected writers who could tailor the story to the star, making it an ‘Alice Faye movie’ or a ‘Betty Grable movie’ … he had songwriters who could compose for his stars’ voices, not necessarily their characters … Alice and Betty could also handle dialogue well and give credible performances, none of which were Oscar worthy, but all of which resonated with audiences, which is all Zanuck wanted.”

While critically overlooked – their journeymen directors were not auteurs, and Zanuck himself classified musicals as ‘entertainments,’ distinct from his prestige dramas – these films were reliable crowd-pleasers through wartime and beyond, and are now reassessed in Dick’s latest critical study, The Golden Age Musicals of Darryl F. Zanuck: The Gentleman Preferred Blondes.

Darryl F. Zanuck in his office at Twentieth Century Fox

Darryl Francis Zanuck was born in Wahoo, Nebraska in 1902. His father, Frank, was a hard-drinking hotel owner of Swiss descent. His parents separated when he was a toddler, and his mother Sarah remarried. After she developed tuberculosis, Darryl moved with Sarah and her new husband – an abusive alcoholic – to Los Angeles. At eight years old he took his first job as a film extra, but his father insisted he return home.

Amid this fraught environment, the strongest influence on Darryl was his maternal grandfather, Henry Torpin, who lived some ninety miles away from Wahoo. When the eleven-year-old boy wrote him a letter describing his train journey from L.A. to Nebraska, Henry sent it to the Oakdale Sentinel. In 1917, on the day before his fifteenth birthday, Darryl lied about his age and joined the Sixth Nebraska Infantry. Another letter to his grandfather, detailing his training at Camp Cody in New Mexico, duly appeared in the same newspaper; and more followed when he joined the war in Europe.

After his discharge in 1919 he went to New York, hoping to emulate his idol, the great short story writer O. Henry. His stay in America’s literary capital was short-lived, and six months later he returned to California, where he sold advertising copy. In 1923 he published a four-story collection, Habit, earning a decent review from the New York Times.

By the mid-1920s, Zanuck was writing movies in Hollywood. Over four years, under his own name and various pseudonyms, he claimed to have written 21 produced feature scenarios; 65 produced two-reel scenarios; and 31 adaptations. In 1924 he pitched the idea for a feature starring canine sensation Rin-Tin-Tin, launching a wildly popular film series. Within three years Zanuck was heading up production at Warner Bros, and helmed Hollywood’s first feature with spoken dialogue. In The Jazz Singer (1927), Al Jolson tells his audience, “Wait a minute! Wait a minute! You ain’t heard nothin’…”

The great star of stage and radio, Fanny Brice, made her screen debut in My Man (1928), and in 1929, Gold Diggers of Broadway, starring Ina Claire, grossed $4 million. In the same year, another theatrical luminary, Marilyn Miller, was lured to Warner’s for Sally. Both films featured colour sequences. However, as the Great Depression spread across America, filmgoers tired of musical spectacles. After a net loss of nearly $8 million in 1931, Warner Bros. made only one musical in the next year.

When Zanuck read Bradford Ropes’ 1932 novel, 42nd Street – detailing the backstage story behind a Broadway musical – he found a way to revive the genre. Unhappy with the initial studio treatment, he commissioned Rian James (an ex-reporter, vaudevillian and stuntman) to write a “racy, pungent script” with Harvard-educated James Seymour. “James and Seymour captured the feverish anticipation that gripped Depression-era Broadway,” Dick writes, “even if it means the humiliation of the ‘cattle call,’ where they exchange wisecracks and size each other up …”

The stellar cast included Dick Powell, Ginger Rogers, George Brent, Una Merkel, and Ruby Keeler as Peggy Sawyer, a fresh-faced nobody who replaces the show’s temperamental leading lady (Bebe Daniels) at the last moment. “Sawyer, you’re going out a youngster,” says director Julian Marsh (Warner Baxter), “but you’ve got to come back a star!”

Despite the film’s note of gritty realism, its finale – staged by Busby Berkeley – is “dazzingly cinematic,” bridging “the gap between Hollywood and Broadway by uniting them on a particular kind of stage: a soundstage.” In the climactic title number, Ruby Keeler appears in a two-piece black-and-white ensemble, “inviting us to the intersection of high- and low-life, ‘where the underworld can meet the elite.’” The set is a simulation of the real 42nd Street, or Hollywood’s idea of what the average filmgoer imagined it to be.

When 42nd Street was released in 1933, Zanuck had left Warner Brothers. While he claimed to have refused to implement studio boss Harry Warner’s across-the-board salary cuts (which were later dropped), he had already agreed – and taken a cut himself – when Joseph M. Schenck, president of United Artists, invited him to form a new independent company.

One of the first Twentieth Century Pictures releases, Broadway Through a Keyhole (1933), was based on a story by radio host Walter Winchell, with nightclub hostess Texas Guinan and crooner Russ Columbo among the cast. As Dick notes, “Zanuck was using an old formula: a mix of melodrama, song and dance, and recognisable performers from the stage and vaudeville.” Other musicals followed a similar path, including Moulin Rouge (1934), starring Constance Bennett; and Folies Bergére (1935), with Maurice Chevalier and Merle Oberon.

The first Fox blondes: Sonja Henie presents Shirley Temple with a pair of ice skates

In 1935, Twentieth Century merged with the ailing Fox Film Corporation (FFC), gaining its own studio lot in the process. Among the stars Zanuck inherited was child actor Shirley Temple. Although her films were not musicals, they usually contained musical numbers; and Shirley memorably danced in several films with Bill ‘Bojangles Robinson.’ The Norwegian champion figure skater Sonja Henie – whom Zanuck signed up after seeing her at an ice show in 1936 – made nine films at the studio. While not a trained singer, dancer or actress, Henie’s performances were buttressed with guest appearances from a wide range of entertainers; and she became one of Hollywood’s highest-paid stars. Arguably her best film, Sun Valley Serenade (1941) includes a non-skating production number with Glenn Miller and His Orchestra rehearsing ‘Chattanooga Choo-Choo,’ ending with some deft toe-tapping by a young Dorothy Dandridge and the Nicholas Brothers.

One of Fox’s newer signings was Alice Faye, a former big band singer and protégée of entertainer Rudy Vallee. “You can bet your last dollar that Faye will be a star,” Zanuck predicted. Like many starlets of this period, she was initially groomed as a platinum blonde in the Jean Harlow mould. As Dick observes, it was probably FFC’s former production chief, Winfield Sheehan, who had the idea to soften her image, “perhaps realising that she would never be a sex symbol … and while she could play tough, she was wholesome tough but never earthy or crass.”

Alice Faye

In Sing, Baby, Sing (1936), she played a debutante who fancies herself a chanteuse. “Alice could do ballads and blues,” Dick writes. “What is truly remarkable is the way she transforms ‘You Turned the Tables on Me’ into a wistful memory.” On the Avenue (1937) is a ‘screwball musical,’ borrowing the ‘runaway bride’ plotline from Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night (1934), and the fast-paced newspaper setting of Metro’s Libelled Lady (1936.) Musically Alice played second fiddle to co-star Eleanor Powell, with whom she duetted on ‘I’ve Got My Love to Keep Me Warm.’ Her one solo number, ‘This Year’s Kisses,’ was “delivered with the air of subdued stoicism that had become her trademark.”

Always keeping a close eye on the competition, Zanuck developed In Old Chicago (1938) to exploit the success of MGM’s San Francisco (1936), which culminated in the 1906 earthquake that destroyed most of the city. Zanuck’s own ‘disaster movie’ revisited the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Heavily fictionalised, In Old Chicago casts Tyrone Power and Don Ameche as the O’Leary brothers, one an ambitious politician who weds singer Belle Fawcett (Faye), and the other a saloon owner who dies in the fire. Although her role was limited, Alice held her own with a “spirited cancan” during the title number, and the nostalgic favourite ‘Carry Me Back to Old Virginny.’

She reunited with Power and Ameche for Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938), with Broadway star Ethel Merman making a foursome. Set to music by Irving Berlin, and directed by Henry King, the film retells the history of jazz. “More than any other film, Alexander’s Ragtime Band revealed Alice’s musical range,” Dick writes. “She had a natural feel for rag as she revealed in both the title song and ‘That International Rag.’ Her voice was made for syncopated music, and her lower range, warm and smoky, was perfect for jazz.”

Her last pairing with Tyrone Power, Rose of Washington Square (1939), was a thinly-disguised semi-biopic of Fanny Brice, who took Zanuck to court. Nonetheless it was the studio’s highest grossing film of that year, with a guest appearance from Al Jolson. Among Alice’s eight numbers, ‘My Man’ was the standout – but too bleak for a finale, with the title song taking its place. She followed this with another musical biopic, Lillian Russell (1940), one of her own favourite roles. “What should have been the finale was Alice’s heartfelt ‘Blue Love Bird,’” Dick writes. “Historical skewering becomes irrelevant when Alice comes on … The contrast between [her] black gown and her white accessories testified to the beauty of monochrome which had a spectrum of its own.”

Alice as Broadway star Lillian Russell

That Night in Rio (1941) was a Technicolor remake of Folies Bergére, with Alice largely overshadowed by Brazilian sensation Carmen Miranda. “Alice will not be particularly remembered for The Great American Broadcast,” Dick writes of her next movie – an all-star tribute to the pioneers of radio – “but it is to Zanuck’s credit that he sought to showcase the art of Black performers like the Nicholas Brothers and the Ink Spots, even though he knew that their scenes would be excised when the film played in the South.” However, many musicals from Hollywood’s golden age featured blackface routines, and Zanuck’s output – spearheaded by Al Jolson’s ‘Mammy’ – was no exception, with several such numbers marring the Technicolor musicals of the 1940s and early ‘50s.

After a year off in which she became a mother, Alice returned in Hello, Frisco, Hello (1943), another vaudeville tale set on the Barbary Coast, featuring what became her signature number (and a wartime standard), the Oscar-winning ‘You’ll Never Know.’ And following the birth of her second child, she played a non-musical role in Otto Preminger’s stylish film noir, Fallen Angel (1945.) Despite her strong performance, she felt betrayed when Zanuck cut some of her scenes in favour of co-star Linda Darnell. Having dropped out of the box-office top ten stars, Alice Faye left movies behind for a successful radio career with bandleader husband Phil Harris.

Betty Grable had been making films since 1929, when at thirteen, she lied about her age and signed her first contract with producer Sam Goldwyn. She briefly worked at RKO, playing supporting roles in two Astaire musicals; and then moved to Paramount, co-starring in Million Dollar Legs (1939) with her first husband, former child actor Jackie Coogan. However, it wasn’t until she appeared in a Broadway hit, DuBarry Was a Lady, that Betty caught Zanuck’s attention.

For her first film at 20th Century Fox, she played a part originally earmarked for Alice Faye. “It is clear that Zanuck thought of Down Argentine Way (1940) as a new type of musical,” Dick writes. Zanuck wanted the musical numbers to be “honest – not so much advancing the plot as enhancing it … The finale was similar to the ending of a stage musical, in which the entire cast would reprise some of the songs after the last bows. Zanuck recreated the essence of a Broadway musical … The typical Broadway musical is in two acts; so are Zanuck’s … MGM may have legitimised the musical as an art form, but it was Zanuck who raised it to the level of theatre … he understood the appeal of ‘naughty, bawdy, gaudy, sporty 42nd Street.’”

In Tin Pan Alley (1940), “a revamped Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” Betty joins Alice Faye in a sister act. In Moon Over Miami (1941) she was teamed with Don Ameche, and another, less fortunate ‘Fox blonde,’ Carole Landis, in a rehash of the studio’s ‘husband-hunting’ comedy, Three Blind Mice (1938). Having danced the rhumba in Down Argentine Way, Betty moved on to the conga in Moon Over Miami. “Betty does both with so much panache that it does not matter who her character is,” Dick writes. “You’re watching Betty Grable.”

Three more Grable musicals appeared in 1943, the year when she topped the annual list of box-office stars. Coney Island was a period piece in which saloon singer Betty becomes a star of the stage (in a reworking of Alice Faye’s Hello, Frisco, Hello), while Sweet Rosie O’Grady became one of her own favourites. Grable remained in the top ten until 1951, making her America’s highest paid woman from 1946-47, and ultimately, one of the most popular female stars of all time. Her films grossed over $100 million. Only a few women, including Joan Crawford, and later Doris Day and Elizabeth Taylor, have matched Betty’s box-office record.

In the patriotic Pin Up Girl (1944) she played a USO entertainer. After a string of hits, Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe (1945) was hampered by the expense of recreating the legendary Manhattan nightspot and the showgirls’ exotic costumes (designed by Charles LeMaire.) Her next film, The Dolly Sisters – a musical biopic of the variety duo, with June Haver as Betty’s sibling – was more popular.

After taking time off to start a family with her second husband, bandleader Harry James, Betty returned in The Shocking Miss Pilgrim (1947), which was actually shot in the winter of 1945. Her suffragette role was a break from type, while the period costumes concealed her famous legs. She was pregnant again while filming Mother Wore Tights, the studio’s third highest-grossing film of 1947. This was her first pairing with Dan Dailey, who became her preferred leading man. They were reunited in When My Baby Smiles at Me (1948.)

Another deviation from the Grable formula, That Lady in Ermine became the studio’s lowest grossing film of 1948. The film was originally planned as a non-musical vehicle for Gene Tierney. The great comedy director, Ernst Lubitsch, envisioned it as an operetta. When he died of a heart attack eight days into production, Otto Preminger replaced him. “Preminger did not have a light touch, and even if he did, Betty could not respond to it,” Dick writes. “She could be brassy and tender, but the high style eluded her …” She worked with another Hollywood auteur, Preston Sturges, on The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend (1949.) Sturges remembered her as “a splendid actress, capable of any role,” and wished that “the story … were one-tenth as good as she is.”

June Haver

Grable wasn’t the only ‘Fox blonde,’ as like many studio heads, Zanuck kept a few starlets in reserve. “When a role called for someone winsome and virginal, Zanuck would give it to June Haver,” Dick writes. “Alice and Betty could never play demure … Zanuck saw June as, if not Betty’s replacement, then as a mirror image, Betty in reverse.” Nicknamed ‘the pocket Grable,’ Haver was a former band singer who broke through in Irish Eyes Are Smiling (1944.) Ostensibly a biopic of songwriter Ernest Ball (Dick Haymes), it was scripted by Damon Runyon, with Haver second-billed as the bonny Irish lass who steals Ball’s heart.

June suited period pieces best, but Zanuck tried her out in Where Do We Go From Here? (1945), a contemporary musical with a time-travel theme, and even a score by Gershwin and Kurt Weill couldn’t rouse public interest. “The charm was there, but the appeal was absent,” Dick says of June’s role in Wake Up and Dream (1945.) “In the very first scene, she is in a server’s uniform, tidying up the diner where she works; but whether in a dress, a shirt and slacks, or jeans, she looked no different from any other ingénue.”

She had moderate success with Three Little Girls in Blue (1946) – the latest reboot of Three Blind Mice, alongside Vivian Blaine and Vera-Ellen – but her career’s momentum was flagging. “Zanuck then realised June could never be Betty’s replacement,” Dick writes. “Betty did not have to appear in a period musical to generate big box-office.” Noting that June’s most popular role was in a Grable film, The Dolly Sisters, he adds: “The draw was Betty, not June … It might have been different if June had made her 20th Century-Fox debut at the same time as Betty. But Betty came first … June arrived too late on the scene to be a pin-up girl, though Zanuck wanted the public to think of her as one.”

Returning to familiar territory, she donned period garb for two more songwriter biopics, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, TCFs fourth biggest money-maker of 1947. She was top-billed for Oh, You Beautiful Doll (1949), but her role was secondary to leading man S.Z. Sakall. Zanuck loaned her out to Warner Brothers for Look for the Silver Lining (1949), a biopic of Broadway star Marilyn Miller; and another period musical, The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady (1950.) Back at the home studio, she starred in I’ll Get By (1950), a remake of Grable’s Tin Pan Alley. A devout Catholic, June briefly joined a convent before returning for her aptly-titled last movie, The Girl Next Door (1953.) A year later, she married actor Fred McMurray and retired from show-business.

If Haver was a ‘Pocket Grable’, Vivian Blaine – like June and Alice Faye, a former band singer – was the ‘Cherry Blonde.’ (She couldn’t be the Strawberry Blonde; that was Rita Hayworth.) Blaine made seven musicals at 20th Century-Fox from 1944-46 before returning to Broadway. Having played the female lead in a Laurel and Hardy comedy, Jitterbugs (1943), she replaced the pregnant Faye in Greenwich Village (1944), a period musical described by Dick as “a synthesis of two familiar plotlines: ‘mounting a show’ and ‘high art vs. popular culture,’ a Zanuck favourite.”

From her first number, Dick writes, Vivian blazed a different trail: “She was not like any other 20th Century-Fox star. Her years as a band singer made her a storyteller in song, delivering the lyrics as if she were experiencing them. Her true medium was the theatre … She was a much better actress than either Betty or June … In terms of performance style, Vivian was closer to Alice Faye and could easily have become her successor if Zanuck had given her the right kind of build-up … Betty and June had generic voices, pleasant but not distinctive … [Blaine] had range, while the others had a scale.”

Something for the Boys (1944), adapted from Cole Porter’s Broadway show, should have been perfect for Vivian. “Until the 1950s, Zanuck never showed much interest in bringing Broadway musicals to the screen,” Dick writes; noting that MGM led the way in stage adaptations, while TCF mythologised Broadway itself. Standing in for Ethel Merman, Vivian played one of three cousins who turn their inherited country pile into a residence for the troops. She was given top billing in Doll Face (1945) – based on The Naked Genius, a story penned by burlesque queen Gypsy Rose Lee, and staged by impresario Mike Todd as a short-lived vehicle for Joan Blondell – and had been originally purchased by Zanuck for Carole Landis. The film was significantly toned down, and its low-budget values showed.

If I’m Lucky (1945) was Vivian’s last film for the studio, and for her co-stars Perry Como and Carmen Miranda as well. It was essentially a remake of Thanks a Million, TCF’s 1935 political satire with music. Standing in for Dick Powell, Como was an unexciting leading man; and black-and-white photography added to the film’s overall drabness. Back in New York, Blaine finally found her niche as ‘Miss Adelaide’ in Guys and Dolls, later recreating the role in the 1955 movie adaptation.

Vivian Blaine

In My Blue Heaven (1950) Betty Grable and Dan Dailey were cast as a husband-and-wife team working in the new medium of television while trying for a baby, with support from David Wayne and (in her movie debut) Mitzi Gaynor. However, Dick argues, “adoption is too serious a subject for a musical.” Victor Mature joined Grable for Wabash Avenue, a Chicago-bound remake of 1943’s Coney Island, and “a brassier and bawdier version that reveals the full range of Betty’s performance style: lowbrow, middlebrow, and highbrow. She shimmies, bumps, high-kicks, sings ballads, dances elegantly …”

Call Me Mister (1951), based on a Broadway revue, was the final Grable-Dailey vehicle, and their weakest. For the remainder of her studio tenure, Betti was set adrift from her most trusted directors (Walter Lang, Irving Cummings, and Henry Koster.) In Meet Me After the Show (1951) she has one memorable number, in which she and Gwen Verdon impersonate street kids dreaming of the high life. “Jules Styne’s music owes much to Ravel’s ‘La Valse,’ with its swirling and restless rhythms suggesting a waltz gone out of control,” Dick writes. “Although ‘I Feel Like Dancing’ is [an] urchin’s reverie, it represents the most sophisticated dancing Betty had ever done. She gives herself completely to her (uncredited) partner who whirls her around so gracefully that they seem to be airborne.”

The Farmer Takes a Wife (1953) was a dated remake of a 1930s comedy, with Betty stepping in for Mitzi Gaynor. This was unfortunate, as at thirty-six Betty was too old for the part; and, Dick adds, the period costumes with their hoop-skirts did not flatter her figure. “Any feminist hoping that the ending of the remake would be more enlightened than the original would have been disappointed,” he writes. The film did not recoup its budget domestically.

Grable’s last hurrah came in the non-musical comedy, How to Marry a Millionaire (1953). At first glance the story of three New York models searching for rich husbands seems reminiscent of Moon Over Miami, but it was based on an earlier Broadway show. While two of the three protagonists were retained, Grable’s role as madcap Loco was lifted from a different play. “Betty never had to share the screen with two women like Lauren [Bacall] and Marilyn [Monroe], who possessed such powerful personas,” Dick writes. Moreover, although Betty was top-billed in the credits, Monroe’s name appeared first in the trailer and she was also more prominent in the advertising. “If [Betty] remained at 20th Century-Fox, it would be more of the same: secondary roles under the guise of leads,” Dick says of her subsequent exit from the studio. “She knew it was time to leave …”

Zanuck on the town in 1953 with Grable, Monroe and Lucille Ball, and columnists Walter Winchell, Jimmy McHugh and Louella Parsons

Her next movie, Columbia’s Three for the Show (1955), was a remake of a Jean Arthur comedy, Too Many Husbands (1940.) Dick suggests that it may have been Fred Karger, Columbia’s music supervisor and voice coach, who persuaded studio boss Harry Cohn to add music, mixing Gershwin standards with “unhummable” new songs, including ‘Down Boy’ (an offcut from TCF’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.) “When Betty performed – or, rather, vamped her way through – […] ‘How Come You Do Me Like You Do,’ she didn’t so much sing the lyrics as purr them,” Dick writes. “It was obvious she was imitating, but not parodying, Marilyn Monroe … If Marilyn performed [the songs], it would have been with her usual feral sensuousness. Betty is just eerily sexy, but it is a feigned sexiness from a woman in her mid-thirties who never had to work so hard to convince a man she loved him.”

Grable with Sheree North in How to Be Very, Very Popular (1955)

Now a freelancer, Grable returned to 20th Century-Fox for How to Be Very, Very Popular (1955), based on She Loves Me Not, a novel turned play – and, in 1943, a Miriam Hopkins movie – whereon a nightclub performer hides out in a men’s college dorm after witnessing a murder. A year before, veteran screenwriter Nunnally Johnson (who also penned How to Marry a Millionaire) had signed a new writer-producer-director contract. One of his first duties was to find a project to reunite Monroe with her Blondes co-star, Jane Russell. When Marilyn refused, Zanuck suspended her and nabbed Betty instead, with another ‘replacement blonde,’ newcomer Sheree North, as her sidekick. “As it turned out, North walked off with the movie after doing ‘Shake, Rattle and Roll,’” Dick writes. “Very few movie careers end in a blaze of glory, and Betty’s was no exception.” She spent the next two decades performing in musical theatre and cabaret, until her death in 1973.

Betty Grable

Marilyn Monroe by Nickolas Muray, 1952

Where Grable ended, Monroe began: but as Dick writes, Zanuck was always ambivalent about the most famous blonde of all. “I hated Marilyn Monroe! I wouldn’t have slept with her if she paid me,” he told biographer Mel Gussow. In 1946, actor turned studio executive Ben Lyon had shown Zanuck her first screen test, and although sceptical of Lyon’s claim that she could be the next Jean Harlow, he gave her a six-month contract.

A year went by and Marilyn had made only two films – including June Haver’s non-musical hit, Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!, in which her part was mostly cut. She was dropped by TCF, but Columbia signed her in early 1948, and she was given the second lead in a low-budget musical, Ladies of the Chorus. As Dick observes, Marilyn did not come from a theatrical background. “But as a model, she understood the camera and knew how to put her body to maximum use,” he writes. “When Marilyn performed ‘Every Baby Needs a Da-da Daddy’ strutting down the runway, it seemed as if she was a regular on the Minsky circuit … Marilyn displayed a voluptuousness that was as natural as it was performative. She was capable of bringing a feline sleekness to a number …”

Fred Karger, whom she briefly dated, nurtured her talent for singing; while acting coach Natasha Lytess tutored her for six more years, although her presence on film sets led to frequent clashes with directors, co-stars, and studio bosses. (Marilyn replaced Lytess with the equally divisive Paula Strasberg in 1956.) Her Columbia stint was also short-lived and by 1949, she was freelancing under the guidance of her agent and mentor, Johnny Hyde.

She returned to TCF for A Ticket to Tomahawk (1950), a comedy Western with Dan Dailey and Anne Baxter. Her part as a showgirl in a travelling troupe was minimal, but she sang and danced alongside Dailey in a musical number, ‘Oh! What a Forward Young Man You Are.’ Following a more sizable role as an ambitious starlet in the Oscar-winning All About Eve, Marilyn made a permanent return to TCF in 1951, playing mostly decorative roles in light comedies like Love Nest, in which her performance as a flirty WAC upstaged June Haver.

“No one at Twentieth Century-Fox appears to have seen Ladies of the Chorus,” Dick writes. “Otherwise, Marilyn would have been welcomed back and groomed as Betty Grable’s successor, which is eventually what happened, but not until 1952.” Instead, Zanuck cast her as a disturbed babysitter in the film noir, Don’t Bother to Knock, having sent her a “glowing note” after viewing her screen test. “As Nell Forbes, Marilyn made paranoia seem normal,” Dick observes. Zanuck then tried her out as an adulterous wife with murder on her mind in Niagara (1953.) “If she was scary as Nell Forbes, she was lethal as Rose Loomis,” Dick writes. Her acting was impressive, but it was in a musical comedy that she finally conquered the box office.

When Zanuck decided to film the 1949 Broadway musical, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, he had promised the lead role of gold-digger Lorelei Lee to Betty Grable. But when he realised that he would have to pay Grable $150,000 – the same amount he had already paid for the rights to the show – he turned to Marilyn instead. Under the terms of her 1951 contract, Marilyn was paid $750 per week (earning $18,000 in total), while co-star Jane Russell – loaned out by RKO’s Howard Hughes – earned top billing and a $200,000 fee.

“The stage version was considerably more sophisticated,” Dick writes, noting that Carol Channing’s Lorelei was “not the original Material Girl but a life-loving flapper,” whose eyes “bespoke an innocence that may have been compromised but not sullied.” The film’s action was transported from the Roaring Twenties to a contemporary milieu. In the play, it was Gus Edmond who sang ‘Bye Bye Baby’ to Lorelei, whose backstory (she once shot a man in self-defence) is largely excised. In the film, ‘Bye Bye Baby’ is a duet for Lorelei and her pal Dorothy (Russell), while Gus (Tommy Noonan) looks on. Similarly, ‘A Little Girl From Little Rock’ became ‘Two Little Girls From Little Rock.’

Those songs, alongside ‘Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,’ were the only survivors from the show’s fifteen-track score. “[Monroe] vamped her way through the number, shaking her hips and endorsing her favourite jewellers by calling out [their names],” Dick writes. “This was a far cry from Carol Channing, who stood alone on stage and sang the song the way it was written.” More than any previous role, Lorelei cemented Marilyn’s public image as a dizzy sex kitten.

As the film’s main title – ‘Howard Hawks’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’ – suggests, Zanuck’s involvement was limited. However, he did instruct screenwriter Charles Lederer to retain two key aspects of the play: Dorothy’s love for Ernie Malone (Elliott Reid), and her “real affection” for Lorelei. (The film’s five musical numbers were supervised by choreographer Jack Cole.)

“And since male bonding is a recurring theme in Hawks’ films, he did not need Zanuck to tell him that bonding could work just as well as well with two females,” Dick writes. “The Lorelei-Dorothy relationship was one that Hawks understood … If there is an air of vulgarity about Lorelei Lee, Hawks was partly responsible for it. He found her ‘colossally dumb and profoundly vulgar,’ which is also the way he perceived the character, Zanuck may have thought so, too, but the characterisation suited the script which depicted Lorelei as a diamond-struck blonde, more calculating than dumb.”

Both Zanuck and Hawks’ comments about Monroe reek of misogyny, and they would not be the last to underestimate her. She made just two more musicals – neither matching the success of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes – though her other films often incorporated songs. (In 1959’s Some Like It Hot, made for United Artists, she performed three jazz-age standards.)

In early 1954, the studio suspended Marilyn when she refused The Girl in Pink Tights. The project was soon shelved, and as part of her contract renegotiation, she agreed to appear in the all-star musical, There’s No Business Like Show Business. A celebration of the Irving Berlin songbook, this would be the second in Ethel Merman’s two-picture deal – the first was 1953’s Call Me Madam – and Merman insisted on top-billing. Marilyn’s character was a late addition to this story of the Five Donahues, a fictional clan of variety performers; initially penned by Lamar Trotti, with Phoebe and Henry Ephron taking over after his death.

As hat-check girl Vicky Parker, Marilyn provides the love interest for young Tim Donahue (Donald O’Connor), but the romance goes awry when she becomes a star in her own right. The main title reads ‘Darryl F. Zanuck Presents/A Cinemascope Production/Irving Berlin’s There’s No Business Like Show Business.’ Despite following the same formula as Zanuck’s past musical triumphs, the $4.430 million production grossed just $4.5 million in domestic rentals.

“There’s No Business Like Show Business might have been a better film with Mitzi Gaynor as Donald O’Connor’s musical partner and June Haver as his sister,” Dick suggests. “Zanuck felt, however, that it needed some sex, first with Sheree North if Marilyn was still baulking about appearing in what was clearly a supporting role … Any musical with Marilyn required the numbers to be tailored to her Lorelei Lee image, which is the only one that the public had of her as a musical performer.”

She had worked well with Jane Russell in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, but here she was ill-at-ease among a cast of musical theatre veterans. The film’s choreographer was Robert Alton, but she retained Jack Cole for her solo numbers – ‘After You Get What You Want (You Don’t Want It’ and ‘Heat Wave’ – and his burlesque stylings seemed out of place in a family-oriented musical. She then sang ‘Lazy’ while lying on a couch, with O’Connor and Gaynor dancing around her.

In 1960, when Marilyn made her last musical, she had not worked at TCF for four years. Norman Krasna’s screenplay can be conceived as “the companion piece to The Prince and the Showgirl, in which Marilyn played an American musical performer who becomes involved with a prince,” Dick writes. “In Let’s Make Love, Marilyn is the star of a musical revue who becomes involved with a billionaire.” For her opening number, Marilyn slides down a pole “in a baggy sweater and black tights … teasing the double entendres out of Cole Porter’s ‘My Heart Belongs to Daddy.’” The song was first heard in Porter’s Broadway musical, Leave It to Me (1938), with leading lady Mary Martin “doing a genteel strip and looking virginally innocent … Martin personified the far side of innocence; Marilyn, the underside of experience.”

As Dick observes, Monroe worked with many great directors, and George Cukor certainly falls into that category. However, their collaboration was ultimately a damp squib. Focusing on the script rather than the musical numbers (choreographed, as always, by Jack Cole.) Cukor’s challenge was to guide Marilyn in making her character’s arc – she is duped into believing the billionaire is an unemployed actor – believable and sympathetic. “This is the kind of narrative made up of layers of deception at which Billy Wilder excelled,” Dick writes. “Cukor, on the other hand, preferred comedies of wit and sophistication …”

A host of A-list actors were considered before Gregory Peck signed on as her leading man, only to withdraw after Marilyn demanded script changes that diminished his role. She then suggested the French singer Yves Montand. “With Montand in the role, the character had to be French, but Montand’s limited command of English made his line readings sound leaden,” Dick writes. “If Wilder were directing, he probably would have sought out Tony Curtis, who did a spot-on imitation of Cary Grant in Some Like It Hot and could sound like Charles Boyer if the character remained French.” Wilder was briefly considered to direct, but rejected the offer; and Curtis and Monroe disliked each other. Today, Let’s Make Love is chiefly remembered for Marilyn’s messy affair with Montand, although the spark between them failed to ignite on the screen.

Despite the failure of Let’s Make Love, Cukor was selected to direct her next TCF film. Something’s Got to Give (1962) was a remake of the romantic comedy, My Favourite Wife (1940.) The title is lifted from a song performed by Fred Astaire in Daddy Long Legs (1955), but although Marilyn and her co-stars Dean Martin and Cyd Charisse had all made musicals, it was never planned as such. By then, she was in fragile health and would ultimately be fired after repeated absences from the set. Monroe died of an overdose that August, while negotiations to reinstate her were still ongoing.

Viewing the extant footage, Dick describes a scene in which she is reunited with her children as “especially touching … the little that was shot indicated that she could handle the role if she had a director like Billy Wilder, who knew that, despite her unpredictable and erratic behaviour, in time he would get a good performance from her.”

While Dick’s commentary on Something’s Got to Give is perceptive, it’s unclear why he chose to highlight an unfinished non-musical, while ignoring River of No Return, an earlier ‘musicalised’ Western with four solo numbers from Marilyn, the most she performed in any film. One of her songs, ‘I’m Gonna File My Claim,’ topped the U.S. Hit Parade in the summer of 1954, proving that her musical forays did not rely solely on her physical charms, so often exploited on the screen.

Monroe wasn’t the first blonde bombshell, nor would she be the last; but her cultural impact was such that every studio moulded starlets in her likeness, often to their detriment. Zanuck had his eye on Sheree North as a possible replacement since There’s No Business Like Show Business. During Marilyn’s extended no-show in 1955, Zanuck thought he had found the next Fox blonde. Sheree North first made her name in Hazel Flagg (1953), a Broadway musical based on the 1937 screwball comedy, Nothing Sacred. After she reprised her ‘Salome’ number in Martin and Lewis’ Living It Up (1954), Nunnally Johnson cast her in How to Be Very, Very Popular – the film Marilyn had wisely rejected – and North’s film career was launched as Betty Grable’s ended.

Over the next three years, Sheree made six more films at 20th Century-Fox, including two musicals: The Best Things in Life Are Free (1956), and Mardi Gras (1958.) In both films, she was billed fourth. “If she had been at MGM, a producer like Arthur Freed or Joe Pasternak might have been able to showcase her talent,” Dick writes. “Her singing voice always had to be dubbed, but as a dancer she would have been a more than worthy partner for Gene Kelly.”

But the Monroe comparisons that landed her on the cover of LIFE magazine were off the mark. “She had the ‘little girl lost’ look that Marilyn could flash but not the mysterious allure that was also part of Marilyn’s persona,” Dick observes. “It was evident as early as 1956 that Zanuck was losing interest … She could never be the new Marilyn because she could only be sensuous, not sexual.” Nonetheless, after leaving the studio in 1958, Sheree worked steadily in plays, movies and television for another forty years.

Sheree North

George Axelrod’s Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? – a satirical reworking of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, set in Hollywood – opened on Broadway in 1955, with Jayne Mansfield playing sex symbol Rita Marlowe. After Zanuck’s departure in 1956, she signed a six-year contract. Her first vehicle, Frank Tashlin’s The Girl Can’t Help It, was a “quasi-musical in CinemaScope” about the music business, starring Tom Ewell as a down-at-heel agent who attempts to make slot-machine racketeer Edmond O’Brien’s girlfriend a pop star. Ewell had previously co-starred with Monroe in The Seven Year Itch (1955), and with Sheree North in The Lieutenant Wore Skirts (1956.)

The Girl Can’t Help It was bolstered with performances from rock ‘n’ rollers, jazz singers, and Ray Anthony’s orchestra. “Unlike Marilyn, Jayne was a platinum blonde who only played the sex kitten when she was with Edmond O’Brien; when she realised how ruthless he was, she stopped purring and denounced him in her natural voice,” Dick writes. “Jayne was quite believable as a competent singer who pretends to have no ear for music […] because she would rather be a wife and mother than a performer … In the end, the charade is over when Jayne sings ‘Ever’ytime’ splendidly, courtesy of Eileen Wilson, her voice double … Ewell and Jayne shared the acting honours, with Ewell giving his best performance as a manipulative agent who discovers his conscience and grows too fond of Jayne to allow her to bullied by a sleazebag like O’Brien.” (Although routinely dubbed in her Fox films, she later embarked on a recording career.)

While a critique of the music business was acceptable in Hollywood, the inside jokes of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? hit a little closer to home, as Tashlin realised when he adapted it for the screen. Agents like Irving ‘Swifty’ Lazar and Lew Wasserman were too powerful to lampoon, and so the movie industry setting was switched to the rival medium of television. The title character, who never appears in the play, becomes Rockwell Hunter (Tony Randall), charged with persuading Mansfield’s character to endorse a product for a commercial.

Randall rises through the ranks to head a talent agency, “not through satanic intervention but rather through luck and perseverance,” Dick writes; but while the agent’s role is sanitised, “Tashlin turned Jayne into a caricature with a giggly squeal, whereas Axelrod’s Rita was a shrewd business woman with her own production company. Anyone who saw Jayne in the original, as did the author, knew that she was an actor playing Rita Marlowe, the sex symbol, who was playing a similar role herself …” Nonetheless, Mansfield’s glitzy persona added a stroke of pop-art verve to Tashlin’s bowdlerised farce, which has since garnered a critical renaissance.

Fox then gave Jayne a dramatic role in The Wayward Bus (1957), “a Grand Hotel on wheels” in which she played Camille, a nightclub dancer, “very much like Marilyn’s Cherie in Bus Stop.” Although this subtle performance earned her a Golden Globe, the film made only a modest profit. She then starred in The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw, a Paleface-style comedy Western with British actor Kenneth More, and her three musical numbers were dubbed by Connie Francis.

While remaining a household name, Mansfield’s knack for ‘puffblicity’ rebounded as the Fifties bombshell craze gave way to the sexual freedom of the Sixties, and she never recaptured her early success onscreen. After her contract was terminated, she continued working in television and cabaret until her fatal car smash in 1967. “Jayne Mansfield was nobody’s fool,” Erik Liberman wrote for the Hollywood Reporter on the 50th anniversary of her death. “Her bid for immortality lives on — not just in the lives of her children, but in a thriving, ‘famous-for-being-famous’ culture she helped to create.”

Mitzi Gaynor

Mitzi Gaynor – described as ‘the blonde exception’ to Zanuck’s parade of leading ladies – is one of the last surviving stars of Hollywood’s golden age. Daughter of a dancer mother and a musician father, she was performing in the Los Angeles Civic Opera at the age of thirteen. In 1950, she made her film debut in My Blue Heaven. Although fifth-billed, she made a strong impression as Betty Grable’s rival, dancing a “torrid routine” with Dan Dailey in their duet, ‘Live Hard, Work Hard, Love Hard’. “By eighteen,” Dick observes, “Mitzi Gaynor was ready for the movies.”

While MGM had a monopoly on composer biopics (The Great Waltz, Till the Clouds Roll By, Three Little Words), Zanuck carved his own niche with nostalgic depictions of great musical performers. Lotta Crabtree, America’s highest paid actress during the 1880s, may have been a favourite of his grandfather. In 1951, he cast Mitzi as Lotta in Golden Girl, her first starring role. Like many biopics, this “disjointed but tuneful” movie was “one-quarter fact and three-quarters fancy.”

“In hindsight, the pro-South sentiments of Golden Girl seem pitifully unenlightened,” Dick admits, noting that in the pre-Civil Rights era, ‘plantation sagas’ that glossed over the grim realities of slavery and racial segregation were still taken at face value by American audiences. “Although Mitzi Gaynor deserved a better script,” he writes, “she revealed a range that would have served her well a decade earlier … [She] was a unique artist. Alice Faye and Betty Grable performed with a burnished professionalism that left you awestruck at such perfection. But they never exhibited the exhilaration that comes from the inner joy of performing … Mitzi revelled in performing and beamed her delight to the camera, which captured it for moviegoers.”

Zanuck was disappointed by Golden Girl’s mediocre domestic intake, as it was unlikely to appeal to European tastes. By the early 1950s the most successful musicals were Broadway imports, and his ‘backstage’ formula was becoming dated. Nonetheless, he forged ahead with three more studio musicals for his new star. Filmed in 1951 but unreleased until 1953, Down Among the Sheltering Palms was no more progressive than Golden Girl. Set during the final years of World War II, the film cast Mitzi in a ‘passing’ role as a Polynesian native who falls for a US Army captain (William Lundigan.) As the Production Code prohibited mixed-race romances, their attraction is never consummated. In an otherwise tepid review for the New York Times, Bosley Crowther praised Mitzi’s way of “stopping the show cold, or hot, as usual.”

Produced by theatrical maestro George Jessel – with author Damon Runyon’s name above the title – Bloodhounds of Broadway (1952) was the only one of Gaynor’s early musicals to make a decent profit. The Prohibition era setting was updated to more recent times, against the backdrop of the Kefauver Committee’s investigation into organised crime, with Mitzi’s character rewritten entirely as a Southern farm-girl who lands in New York. “The musical numbers revealed the full range of Mitzi’s talents,” Dick reflects. “She could invest a dreamy ballad like ‘I Wish I Knew’ with a sincerity that stops short of heartbreak. She can go from parodying her Georgia cracker image in ‘Bye Low’ to a sultry ‘Jack o’ Diamonds’ in orange and black tights and a pale blue feather boa.”

In The I Don’t Care Girl (1953) she played Eva Tanguay, whose racy performances made her the ‘Queen of Vaudeville’ at the turn of the 20th century. “That aspect of the story came through in Jack Cole’s eroticised choreography, but not in the bland story,” Dick writes. “Mitzi had to alternate between playing an ingénue in love with a married man and a fiery entertainer who sheds her inhibitions in performance. Jack Cole’s choreography, anachronistic as it was, at least suggested the kind of sensation that Eva created on stage.”

For the title number – set to a ‘jungle beat’ – Mitzi donned a sequined leotard originally designed for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (and later reused in How to Be Very, Very Popular.) “Mitzi looked like an exotic bird in black tights with a white mesh top and a headpiece of black feathers that matched the ones jutting from her hips,” Dick observes. “She poses defiantly and even dives into a pool, all the while declaring her indifference to convention. As can only happen in film, she changes from black to red in the (literally) fiery finale, where, amid artificial flames, she ends her declaration of independence. That sequence, more than any other in the movie, distilled the essence of Eva Tanguay in a number that she could never have performed in real life, but that Mitzi Gaynor could in a display of unapologetic sex. No one, not even Betty Grable or Sheree North, could have expressed contempt for convention with such naked defiance.”

“But Zanuck could not find a real star-defining vehicle for her,” Dick continues. “It certainly was not There’s No Business Like Show Business, in which Marilyn usurped the spotlight whenever she could.” In 1956, Mitzi moved to Paramount for three more musicals, and then made Les Girls (1957) at MGM. This gave her the opportunity to dance with Gene Kelly, but she was outshone by leading lady Kay Kendall. Then came her most popular film, South Pacific (1958), in which she played nurse Nellie Forbush. Mary Martin, who originated the role on Broadway, was considered too old for the screen; and Mitzi was cast after Elizabeth Taylor failed the audition.

After three more films, she returned to the stage, recorded albums, and drew large audiences for a series of TV showcases during the 1960s and ’70s. She was married for 52 years to producer Jack Bean, who managed her career until his death in 2006. Having recently celebrated her 92nd birthday, the indefatigable Ms. Gaynor still makes occasional public appearances and even has a social media presence.

When Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! opened on Broadway in 1943, a new standard was set in which musical numbers became intrinsic to the show’s story. Zanuck became the first studio head to hire the duo for State Fair, a folksy family saga based on a non-musical FFC picture from 1933. “He paid us a lot of money and acceded to our working conditions,” Richard Rodgers recalled, “but he wanted the satisfaction of making us do as he wished.”

Among the leading players, Dick Haymes and Vivian Blaine were proficient musical performers, but the film’s two younger stars, Dana Andrews and Jeanne Crain, were both dubbed. State Fair was TCF’s second highest-grossing film of 1945, and although its score didn’t rise to Oklahoma’s heights, ‘It Might as Well Be Spring’ won the Academy Award for Best Original Song.

The composers’ next show, Carousel, opened on Broadway in 1945, while Oklahoma! was still running nearby, and State Fair filled cinemas nationwide. Zanuck was immediately drawn to Carousel, perhaps identifying with its antihero, carnival barker Billy Bigelow. He suggested Frank Sinatra for the lead, opposite either Judy Garland, Jean Simmons or Doris Day. “Zanuck was not always spot on when it came to casting,” Dick writes, pointing out that the part required a lyric baritone like Howard Keel, not a crooner. Sinatra turned down the role, and Zanuck ultimately agreed to cast Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones, fresh from their success in the 1955 screen adaptation of Oklahoma!

The play ends in Billy’s suicide; but this would have incurred the wrath of the National Legion of Decency, a powerful lobby group for movie censorship. In the film he dies accidentally, with the story told in flashback. Shooting the film in the short-lived widescreen process, CinemaScope 55, only added to the problems on-set. Released in 1956, Carousel was not a hit with moviegoers; and the film is omitted entirely from Rodgers’ memoir, while Zanuck also overlooked it in conversation with his biographer, Mel Gussow.

Preoccupied with Carousel, Zanuck had little involvement in The King and I (1956), although the first title reads, ‘Darryl F. Zanuck Presents …’ He had read Margaret Landon’s novel, Anna and the King of Siam, and produced a non-musical adaptation in 1946. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I opened on Broadway in 1951; the film, starring Deborah Kerr and Yul Brynner, was TCF’s highest-grossing of 1956. It was also the studio’s last musical under Zanuck’s watch. Three months before its release he left Hollywood for Europe, and spent the next few years making films under his DFZ Productions banner, distributed by TCF. At 53, he was recently separated from his wife of thirty years and in the grip of a very public midlife crisis, pursuing doomed affairs with his brunette protégées.

Darryl F. Zanuck with Marilyn Monroe, 1954

Hollywood’s studio system was under increasing pressure from newly empowered stars and their agents, and TCF’s handful of unremarkable musicals produced after 1956 included Mardi Gras, with Pat Boone; Marilyn Monroe’s penultimate movie, Let’s Make Love; and in 1962, a third remake of State Fair. By then, the spiralling costs of Cleopatra – and the scandalous Taylor-Burton affair – had brought the studio close to bankruptcy.

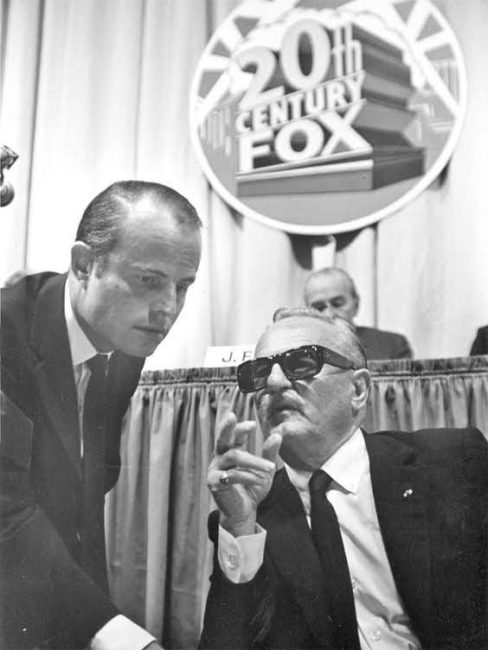

The release of Zanuck’s World War II epic, The Longest Day, marked his return as a Hollywood power player. In July 1962 he replaced Spyros Skouras as president of Twentieth Century-Fox, with his son, Richard D. Zanuck, taking his old position as Vice President, and head of production.

When the final Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, The Sound of Music, opened on Broadway in 1960, TCF bought the rights for $1.5 million. The film was released in 1965, and within a year, The Sound of Music became the highest-grossing movie of all time. Richard Zanuck followed this with three more musicals; Doctor Doolittle (1967), Star! (1968), and Funny Girl (1969.) This gambit failed, and while TCF had hits with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, M.A.S.H., and Patton, the musicals were box-office disasters.

Zanuck Sr. resigned as president of TCF in 1969, and became chairman of the board of directors. By 1970, the studio’s deficit had reached $77.4 million. His son, who had briefly replaced him as president, was fired. While Richard Zanuck went on to co-produce hit films like The Sting and Jaws at Universal in partnership with David Brown, his father’s long career at Twentieth Century-Fox was nearly over.

Zanuck with his son, Richard

In 1972, Darryl underwent surgery for cancer of the jaw. His memory was failing, and after a belated reconciliation, his wife Virginia cared for him in his final years. Zanuck died of pneumonia in 1979, with Hollywood maverick Orson Welles – who remembered him as tough, but never cruel or vindictive – delivering the eulogy at his funeral. “Darryl’s commitment was always to the story,” Welles said. “For Darryl, that is what it was to make a film, to tell a story.”

While planning Alexander’s Ragtime Band in 1938, Zanuck had looked for ways of “dropping in fifteen or twenty of [Irving Berlin’s] famous songs and working our story so that these songs could come in.” At a story conference for Moon Over Miami in 1940, he advised, “We don’t want to make any effort to explain the music or prepare for it.” In other words, a Zanuck musical differed from a non-musical only in the script was treated musically. During another story conference, for Sonja Henie starrer Iceland in 1941, he remarked that if the story needed shoring up, “load it with music.” And in 1954, while considering a movie about the Queen of Sheba for Marilyn Monroe, he told producer Sam Engel: “Like everything else, it depends on the story we create and the showmanship we employ.”

“Zanuck’s musicals were unlike those of any other studio,” Dick concludes. “They no more aspired to high art than Zanuck did when he began his career as a writer of fiction … Zanuck sought to recreate the Broadway stage, as perceived by the popular imagination, in show-business musicals, which could never have been staged in any theatre but only on a soundstage. Still, you had the feeling you were watching a stage show with reprises in the finale, capped by a fade-out curtain call … In his musicals, Zanuck, the lover of spectacle, and Zanuck, the lover of symmetry, became one.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.