Tags

'I Never Took a Lesson in My Life', Arthur Miller, Colleen Townsend, Diana Herbert, Dream Girl: The Making of Marilyn Monroe, Driving Miss Daisy, Endometriosis, F. Hugh Herbert, Helena Sorrell, House Un-American Activities Committee, Ian Ayres, John Gilmore, Johnny Hyde, Let's Make It Legal, Lon McCallister, Marilyn Monroe, Marilyn Remembered, Natalie Wood, Robert Karnes, Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!, Strictly for Kicks, Summer Lightning, Twentieth Century Fox, Walter Winchell, Warrensburg

Actress Diana Herbert, who met Marilyn Monroe on the set of her first movie, died aged 95 in Los Angeles on May 3, 2023.

She was born in Beverly Hills on Christmas Day, 1928. Her father, F. Hugh Herbert, was an Austrian-born screenwriter whose credits included The Cardboard Lover (1928), Vanity Fair (1932), and My Heart Belongs to Daddy (1942.) His Broadway hit, Kiss and Tell, became a 1945 movie vehicle for 17-year-old Shirley Temple.

Diana graduated from Fairfax High School and enrolled at UCLA. In 1946, she made her screen debut with an uncredited bit part as a student in Twentieth Century-Fox’s Margie, a romantic comedy penned by her father and starring Jeanne Crain as a schoolgirl infatuated with her French teacher. Set in a Midwestern high-school in the 1920s, the film was partly shot at the University of Nevada in Reno.

In the spring of 1947, Hugh Herbert directed his first movie at Fox, which he had adapted from a novel by George Agnew Chamberlain (best-known for The Red House.) The film’s unusual title – Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! – refers to a mule-driver’s commands for left and right. In this mostly light-hearted tale of rural life, Lon McCallister plays Snug, a farmhand in love with farmer’s daughter Rad (June Haver.) Snug buys two mules from the farmer and trains them with the help of a veteran mule-driver.

In addition to the two young leads, the film boasted a lively performance from nine year-old Natalie Wood as Rad’s kid sister, and some notable character actors, such as Walter Brennan and Anne Revere. As the film went into production, one of the studio’s recent signings – twenty year-old Marilyn Monroe – was given a small role as Betty, a friend of Rad. Her initial six-month contract from September 1946 had been renewed in February, and like Diana, she was taking classes at the Fox drama school, taught by Helena Sorrell.

Marilyn Monroe in class with Helena Sorrell, 1947 (Photo by Dave Cicero)

“I was attending Miss Sorrell’s classes because of my father, ” Diana told John Gilmore, author of Inside Marilyn Monroe: A Memoir (2007.) “I wanted to be an actress more than anything in the world, but I really wanted to be on the stage – in New York, this marvellous door open for me through my dad.” Marilyn was also a child of Hollywood, although her connections to the movie industry were more humble than Diana’s – her mother once worked as a film cutter, and she began her career as a model.

“My father’s picture was Marilyn’s first,” Diana recalled. “She was a scared rabbit. The front office had dismissed her and thought of her – if they ever thought of her – in a way that was subliminal and would undermine her confidence. Once they felt they had a player’s confidence diminished, they’d be less demanding and aggressive and maybe satisfied being a stable player. They thought of Marilyn as just the scatterbrain daydreamer they believed her to be. They called her a frump. I wasn’t sure what a frump was, but soon realised it was someone who couldn’t take a stand and could be counted on to deliver what you wanted while the using was good. Soon as it dried up they’d be through with her as they had been with hundreds of people. So they were saying she’s a frump and certainly one of the best frumps and maybe she’d prove a goose that’d lay some fourteen-karat eggs, frump or no frump.”

A cast photo shows Marilyn with director F. Hugh Herbert and leading lady June Haver

“It was during the shooting of Scudda Hoo, Marilyn’s first picture, that she sort of sidled up to me, like girl to girl,” Diana said. “It was like we were sharing some secrets we had to keep from the rest of the world. We’d go to the commissary and she wouldn’t talk to other people, just kind of all gathered in. If she did say hello it was like she was embarrassed. I really honestly couldn’t determine if it was a case of drastic shyness – and there was that, yes – or more of a fear to be overheard, like she was going to share a dastardly secret, and if she let truth be known, we’d explode or something …”

Marilyn’s background scenes for Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!

Marilyn had just one line in the movie. Wearing a blue pinafore over a white blouse, she appears as part of a congregation leaving church. ‘Hi, Rad!’ she says, smiling, and a slightly distracted June Haver replies, ‘Oh, hi Betty.’ Her screen-time is less than two seconds. She also filmed a second scene, in which Betty is seen rowing a boat on a lake with another friend, played by Colleen Townsend. Unfortunately, her part in this scene was cut, although the boat and its two occupants can still be glimpsed in the background.

Marilyn with Colleen Townsend in the boating scene

Still photos showing the cut sequence

In his 2003 book, Blonde Heat: The Sizzling Screen Career of Marilyn Monroe, Richard Buskin consulted the original shooting script to reconstruct Marilyn’s second scene; and publicity photos also show her with June (Townsend) – they’re briefly described as ‘a couple of pretty bobby-soxers’ – approaching the dock, where Snug’s stepbrother, Stretch (Robert Karnes) is sunning himself.

BETTY (gayly): Hi, Stretch.

STRETCH (drawling): Hi, Betty – Hi, June.

JUNE (coyly): Is it all right with you if we swim off your dock?

With one bare foot, Stretch shoves the nose of the boat out into the stream again.

STRETCH (grinning): No – it ain’t.

BETTY: Ah, Stretch – why not?

STRETCH: You’re too young. Come back in a couple of years’ time.

Giggling, the two kids pull out of the shot.

“On the sly, but with my father’s OK, I snuck Marilyn into a screening room where he was viewing for editing, and Marilyn got to see herself in the bit part before it was trimmed from the picture,” Diana told John Gilmore. “She’d had one line and whispered to me, ‘Do I sound that awful?’ There wasn’t anything awful about it at all. I said she had a lovely voice – soft and appealing. My father, using the old adage, told me that Marilyn photographed like a million dollars. He told me she was going to be a big star if they didn’t crowd or rush her into it. He said she had every ingredient for it built right into her by nature.”

Marilyn rehearses with Robert Karnes, Lon McCallister, and Colleen Townsend

The cutting of Marilyn’s boating scene was disappointing for Diana too, as she had also appeared in it. “We photographed pretty well because we were so different in personalities, and it showed somehow,” she said of herself and Marilyn, but “there was never any favouritism.” Marilyn was then given another bit part in a B-movie, Dangerous Years, but her contract was not renewed a second time.

Marilyn and Diana Herbert steering the canoe

“Marilyn couldn’t defend herself well,” Diana said. “She didn’t know how to play the game at the studio – the like ‘who’s on top today’ kind of thing. She figured they’d come to her but what happens when you adopt that attitude is they forget about you until the bookkeeper says it’s time to clean out the stables. They cleaned them out and almost as soon as she thought she’d be getting another part, the sons of bitches didn’t pick up her option. She was out of a job.”

Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! Cost $1,680,000 to make, and was filmed in Technicolor. It was held back for several months after Dangerous Years – despite being her first movie – and she was credited last, following Colleen Townsend, as ‘Girl Friend’. Alongside A Ticket to Tomahawk (1950), Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay is the only one of her early films not made in black and white. Not until her starring role in Niagara (1953) would she be seen in colour again.

An image from Marilyn’s ‘babysitter’ layout for photographer Dave Cicero

Marilyn would be seen wearing Betty’s churchgoing attire for a studio publicity stunt which appeared in newspapers across the country in June 1947. Claiming she had been ‘discovered’ while babysitting at a film executive’s home, a series of photos by Dave Cicero showed Marilyn reading a story to a young girl, and putting a baby to bed. In fact, she had been a successful model before landing the contract.

During her first year at Fox, she also posed for LIFE photographer Loomis Dean on the set of Sitting Pretty, alongside arch leading man Clifton Webb (who later became a friend) and another starlet, Laurette Luez. Adapted by Hugh Herbert from Gwen Davenport’s novel, Belvedere, the film starred Webb as a curmudgeonly bachelor who works as a nanny to a chaotic family while writing a tell-all book on life in their wealthy neighbourhood.

Marilyn and Laurette Luez share a couch – and candy – with actor Clifton Webb, in an unused publicity shot for Sitting Pretty (Photo by Loomis Dean/LIFE)

Monroe biographer Lois Banner speculated that she might have been under consideration for a part, but neither Marilyn or Luez appeared in the film – and the rather odd layout, in which the two starlets sidle up to Webb on a couch, went unpublished for many years. Nonetheless, Webb’s eccentric performance earned him an Oscar nomination, and he reprised the role in two more films.

Ahead of its release in April 1948, Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! premiered in 200 cinemas across the Midwest cities of Iowa, Nebraska, Missouri and Kansas, as befitted its bucolic theme. The film grossed $2 million in its first run, and was renamed Summer Lightning (the original working title) for its British release. Although largely forgotten today – other than for giving Marilyn her first role – Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! can be seen on a cinema marquee in a scene from the Oscar-winning 1989 film, Driving Miss Daisy. As Richard Buskin reflects: “What a fuss! Never has so much importance been attached to a couple of donkeys.”

Marilyn signed a new six-month contract with Columbia Pictures in March, but still found time to appear in Strictly for Kicks, a talent showcase at the Fox Studio Club Little Theatre, despite having been dropped almost a year before. “Marilyn and I came together when I was preparing, for weeks it seemed, a song I’d sing at a talent show for the rest of the studio,” Diana said. “I wanted to sing ‘Johnny One-Note’ from Rodgers and Hart’s Babes in Arms, but they had me singing ‘I Never Took a Lesson in My Life.’ They were giving Marilyn the push, but I was heart-sunk, and then surprised because so was Marilyn, heart-sunk that she was doing the song I’d worked so hard on, and heart-sunk that she’d be performing ‘for all those people,’ as she put it, singing a song she didn’t know. She asked if I’d help her learn the lyrics in time. Maybe someone else would’ve been mad about her being put in their place but she was so genuinely sad about it I felt sorry for her – not even for myself.”

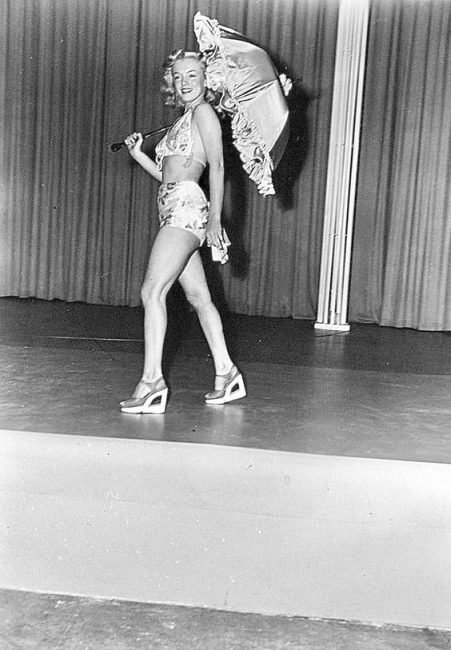

Marilyn was featured in two short scenes, and was photographed onstage in a two-piece, floral-print bathing suit and sandals. She had worn the same ensemble in a publicity shoot to promote Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! ‘I Never Took a Lesson in My Life’ was a popular 1940 song recorded by artists including Stella Moya, Meredith Blake, and the Glenn Miller Orchestra.

Marilyn onstage in Strictly for Kicks (1948)

Before leaving for New York, Diana invited Marilyn to a pool party at her home in Bel Air. “The other guests were mostly young like all of us, and they knew who Marilyn was – the publicity and magazines, plus the couple other pictures she was working in,” Diana said. “Everyone at the party showed their excitement about Marilyn showing up – especially in a bathing suit and swimming with them.” However, Marilyn was running habitually late – and she would soon be well-known for her chronic tardiness.

“I’d told them she was a friend, and they were looking at me with raised eyebrows,” Diana recalled. “Some of them were still swimming, but most had left the pool for the buffet supper. Somehow Marilyn appeared, having come in through the back way to the property, and she was off behind the dressing room across from the pool. She said she was sorry and I said that was fine, but she said she’d forgotten her bathing suit. I said that was okay, too, because I had a brand new suit she could use. She said, ‘Oh, fine,’ and she’d change into it in the dressing room.”

“So far, no one else had seen her, having wandered from the pool and up to the house. Two or three were still splashing around, and I had to go to the house and see to the party. I thought it was strange that Marilyn was taking so long changing into a bathing suit. What was she going to do – be swimming by herself? It was so late already. People were enjoying the buffet, and they’d kept saying, Oh sure, sure, where’s Marilyn Monroe? Laughing about it, like I’d made it up. Two or three times I went down to the dressing room and knocked on the door. I asked if she was all right. Was she coming out? She’d speak close to the side of the door, saying she’d be right out. ‘Oh, yes, I’m coming right out,’ she’d say.”

“She didn’t come out, and I have to confess I was worried and for more than an hour and a half, Marilyn was alone in the dressing room. God knows what was taking her so long. And then – then – she disappeared. She wasn’t there anymore. She’d snuck out and taken off around the back of the house to wherever she’d parked her car – if in fact she’d parked a car. I don’t know. What I know is that she came to the party and nobody saw her, and then she stayed for almost two hours alone in the pool dressing room. Didn’t even put on the bathing suit. I have no idea what she’d been doing there. Sitting? Standing? Waiting for what? Afraid to come out? Alone and responding to me in that hushed tone that she’d be right out, and she never came out, except to disappear.”

Marilyn with Lon McCallister in New York, 1949

While promoting Love Happy on her first east coast tour in 1949, Marilyn joined a group of actors – including Scudda Hoo’s Lon McCallister – to present a ‘Dream House’ in Warrensburg, New York to the winner of a Photoplay magazine contest. Before long, she had learned to ‘play the game’ and was being groomed for stardom by her powerful agent, Johnny Hyde.

Hugh Herbert enjoyed another Broadway success in 1951 with The Moon is Blue, a risqué comedy which director Otto Preminger would bring to the big screen two years later. He also co-wrote Let’s Make It Legal with I.A.L. Diamond, starring Claudette Colbert and MacDonald Carey. Now reinstated at Twentieth Century-Fox, Marilyn Monroe played a gold-digger vying for Carey’s affections – one of several minor films that would help to establish her as Hollywood’s leading glamour girl.

Marilyn during filming of Let’s Make It Legal (1951)

Meanwhile, Diana had made her Broadway debut at Henry Miller’s Theatre (now the Stephen Sondheim Theatre), replacing June Lockhart in For Love or Money, a play by her father. She would reprise her ingénue role in a 1952 episode of Broadway Television Theatre, a syndicated anthology series produced by WOR-TV. When not performing onstage in The Number (1951), for which she won a Theatre World award, and the 1953 musical, Wonderful Town – both directed by Broadway maestro George Abbott – Diana played further roles in television shows such as The Doctor and Man of Crime.

By 1955, she was married to NBC comedy writer and songwriter Larry Markes, and expecting the first of their four children. “They were living in the East 60s, but Diana was hanging out at Sardi’s [restaurant] with actor and ex-boyfriend Sam Levene – or Ralph Meeker or Bob Webber,” John Gilmore wrote. In Diana’s words, they were “wonderful, intense, romantic relationships, and then I had to set them aside because I wanted a family. Sam Levene and I had done a Broadway show, fallen in love and even talked about getting married. Of course it didn’t work out, but Sam and I stayed close friends. We’d talk about shows, though since I’d gotten pregnant I was pretty much side-stepping getting on stage.”

Diana Herbert

Publicity shot, 1950

Via NYPL

“I remember in Sardi’s talking about Marilyn and how much Fox was bringing in on The Seven Year Itch,” Diana added. “Then Sam said he understood the situation she’d had with Johnny Hyde – trading sex for a trip to the moon. “That’s how the game goes,’ I said, ‘and you damn well know it, Sam.’ I said when you live in Hollywood half your life, you accept how the game’s played. Sam was smiling and something about a rose under any other name. We both laughed.”

Frustrated with her limited choice of roles and that her salary wasn’t keeping pace with her box-office appeal, Marilyn had walked out on her contract and moved to New York in late 1954. During her year-long dispute with Fox, Marilyn took classes at the Actors Studio and founded an independent production company. She was also dating playwright Arthur Miller, whose liberal politics made him a target of the notorious House Un-American House Activities Committee (HUAC.)

Marilyn goes ‘incognito’ in New York, 1955 (Photos by James Haspiel)

“I was eight months pregnant as all get-out when I ran into Marilyn by the subway entrance on 58th Street,” Diana recalled. “I said, ‘Marilyn!’ and she looked around confused and nervous at my calling her out of the blue. You wouldn’t have known it was her from the way she had herself covered up with that scarf and sunglasses. I said, ‘Scudda hoo! Scudda hay!’ Then she grabbed my hand and asked me who I was. I said, ‘I’m Diana, for God’s sake,’ and I sang a line from ‘I Never Took a Lesson in My Life.’ She said, ‘But you’re pregnant! Look at you – you’re so pregnant,’ and I said, ‘Well, I hope so!’”

“Minutes later she led me half a block over by Carnegie to a little, tiny Greek restaurant. They had a couple tables and we sat in the corner where it was darkest. I told her I’d changed my diet and was sticking close to food that was good for me and the baby. I guess we talked and then a tear ran down her cheek from under the sunglasses. She said she admired me so much and was so envious it was making her cry.”

“We had coffee and a little something, a kind of Greek cake, but she kept looking out the window at the street and I asked if she was expecting someone, which I assumed was the reason she’d led me to that particular restaurant. She said, ‘No one I want to be expecting.’ I didn’t know what she meant, and she said, ‘They’re spies.’ I said, ‘Spies? What spies?’ She got a funny look and for just an instant I thought, my God, maybe Marilyn’s gone off the deep end.”

“She stared at me closely and said, ‘You must not say anything, but there are federal agents following me.’ ‘Federal agents?’ I said. Marilyn said it was the FBI, because of Arthur’s past affiliations with people the agents considered to have connections with communists. ‘They think he’s still associated with subversives,’ she said, ‘and now that I am with him they suspect I’m a subversive of some sort.’ I said ‘If that’s true, Marilyn, it’s idiotic.’ Then I said, ‘You’re not, are you?’ She said of course not, and agreed it was idiotic but told me she had to watch herself. Slyly, she said she’d become adept at giving them the slip. I asked, ‘How long has this been going on?’ Months, she said. I was shocked.”

“She said a young actor had told her he’d been questioned because he sympathised with liberal elements that the FBI said were associated with leftist sympathisers. ‘They’d put him in a car like he was a criminal and made him show them places he’d been and they wanted to know if Arthur had been there, and if I had been with him.’ The actor, she said, told her they’d questioned him about Arthur and about her, and what connection she had with any associations through Arthur.”

In fact, Marilyn’s suspicions were not unfounded. Her FBI records show that the FBI began monitoring her in 1956, when her relationship with Arthur was first reported, until her death in 1962. Many actors, writers and directors had been blacklisted in Hollywood while others chose to save their careers by naming names. After Joe McCarthy, head of HUAC, was censured by the US Senate in 1954, the Committee lost credibility. By targeting America’s leading playwright, they hoped to regain momentum.

Marilyn and husband Arthur Miller, 1957

In his autobiography, Timebends, Miller wrote that the Committee’s chairman offered to drop the charges if Marilyn agreed to be photographed with him. Miller demurred, and having also refused to name names, was convicted for contempt of Congress. Marilyn, who married Arthur in 1956, supported him throughout his two-year legal battle, and the conviction was ultimately overturned.

“Marilyn was sniffing again and kept a hankie against her nose,” Diana recalled. “She said I was so blessed to be having a baby, and she’d wanted a baby more than anything. She said if she could have a baby it would change her life, and I said, ‘You will, Marilyn, it’ll happen. Give it time -’ She said no, she didn’t think she could have a baby. For a second I thought she was saying that getting pregnant and having a child would interfere with her career, which it would, and I was about to tell her how I felt, but she said, ‘I’ll tell you something you must never ever repeat’ and ‘please,’ and did I promise? I said of course. If I told anyone, she said, ‘it would become a fucking circus …’ I swore it would go no further than the coffee cup.”

“She said she had a problem that caused her severe pain and anguish – ‘for years,’ she said, ‘there’s nothing I can do about it …’ It was the reason she was sick and couldn’t have a family. The reason for so many problems in her life and I was so fortunate to be a ‘normal’ person. She said her life was not normal, and it never would be and all she could do about it was try and stop the pain.” Marilyn excused herself and disappeared into the little restroom. “She was gone perhaps twenty minutes to half an hour,” Diana said, “and that reminded me of when she’d hid in our pool dressing room back in Bel Air.” When she came back to the table, Diana asked if she felt better and the answer was a hushed but emphatic “No!”

Marilyn had endured severe menstrual pain since puberty, and while no official diagnosis has emerged, it’s widely thought she suffered from endometriosis. She underwent at least three surgeries to relieve the condition, and narrowly survived an ectopic pregnancy in 1957, followed by a second miscarriage in 1958. These physical symptoms, and the anxiety she experienced, may have worsened her bouts of depression and increasing dependency on prescribed drugs.

“She seemed afraid,” Diana remembered. “Kept looking around, and towards the street, and then she said, ‘You know who is behind this, don’t you?’ I wasn’t sure what she was saying, but then she said, ‘That dirty old man, Winchell!”

“Walter Winchell?” Diana asked, to which Marilyn replied, “Who else? He’s the one responsible for the FBI following us!” Winchell was a gossip columnist, radio presenter and virulent anti-communist. A friend of Marilyn’s ex-husband, Joe DiMaggio, Winchell had also been the first to report on her affair with Arthur Miller. Marilyn claimed that his daughter was a ‘compulsive lesbian’ and that Winchell had wanted to discuss the issue, but then made advances to Marilyn – even though she was sick and in pain.

Marilyn and Walter Winchell, 1953

Marilyn added that Winchell had told J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, about her relationship with Miller. Sexual harassment was a widespread problem in Hollywood long before the age of MeToo, and in a repressed society where homosexuality was still illegal, Marilyn was terrified of being linked to lesbianism – a phobia she would later discuss with her psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson.

“Marilyn wasn’t trying to say Winchell was offering his toad daughter in exchange for calling off the Feds,” John Gilmore added. “Winchell couldn’t have done that anyway, he didn’t have that kind of clout. He was kind of a stooge for Hoover in exchange for favours. Winchell was disgusted with his daughter … [but] naturally no one was going to make a gossip trip out of it – they would’ve been crucified. People were afraid of Winchell, and Winchell hated Arthur Miller for not being a ‘true-blue son of America’ … Winchell was trying to cosy up to Marilyn for ‘hot tips’, thinking he could charm her into slips … Never worked. Marilyn was not a dummy …”

“I was alarmed and I have to say kind of frightened how Marilyn seemed or what was eating her,” Diana admitted to Gilmore. “I wasn’t convinced that she hadn’t become a little mentally unbalanced by all the pressure she was under … I just didn’t know. I had my baby, and then I had three more – a beautiful, artistic family, but I’ve never stopped thinking about poor Marilyn and the baby she wanted so badly … There is so much she gave us, and so little she ever had for herself – and so little that we ever gave her.”

Diana with Stafford Repp in TV’s The Ghost & Mrs. Muir (1968)

Diana returned to the big screen with a small part in teen crime drama, Four Boys and a Gun (1957.) After her father’s death in 1959 she moved back to Los Angeles, where husband Larry Markes worked as a screenwriter. By the end of the decade, Diana was acting again in popular TV shows like The Ghost & Mrs Muir and The Flying Nun. An uncredited appearance in the disaster movie, Airport (1974), was followed by further TV spots in Matt Helm, Police Woman, and Three’s Company.

She divorced Larry Markes in 1978, and married Gene Levitt, creator of TV’s Fantasy Island, in 1985. She later appeared in Welcome to Hollywood (1990), written by her son, Tony Markes. After her second husband’s death in 1999, she continued making occasional short films, and was a regular guest speaker at the annual services held by the Marilyn Remembered fan club at Westwood Memorial Park.

“Marilyn had an aura, there was no doubt about it,” Diana said in 2005. “But the gloss often turned to dross because of her unreliability… she sometimes seemed overwhelmed. When I think about Marilyn I do so with a sense of gratitude as I feel happy to have known her before the peroxide blonde hair and the whole full nine yards.”

Diana at Westwood Memorial Park in Los Angeles in 2013, for a service commemorating the 51st anniversary of Marilyn’s death (via Buzzfeed)

Diana was also interviewed for the feature-length documentary, Dream Girl: The Making of Marilyn Monroe (2022.) “Marilyn was really with it,” she told director Ian Ayres. “When she talked to you, she was really with you, no ifs, ands or buts. No one interfered … She was so warm, open and inviting.”

“The thing that was fun to watch about Marilyn was her transformation, and it happened often during our friendship – you know, the real self, the kind of kid, the girl – and then when she knew that attention was focused on her, and that she was expected to be Marilyn Monroe, the emerging star, she would change … and I would see a little flicker of annoyance when she had to leave being the kid, and become the movie star.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.