Tags

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Barbara Leaming, Bert Stern, C. David Heymann, David Stenn, Diana Vreeland, Donald McGovern, Dr. Marianne Kris, Ethel Kennedy, Frank Sinatra, George Smathers, Happy Birthday Mr. President, J. Randy Taraborrelli, Jacqueline Kennedy, Jamie Auchincloss, Jean Harlow, John F. Kennedy, John F. Kennedy Jr., Judith Campbell Exner, Kitty Kelley, Madonna, Marilyn Monroe, Norman Mailer, Patricia Kennedy Lawford, Peter Lawford, Ralph Roberts, Robert F. Kennedy, Sam Giancana, Scott Fortner, William Kuhn

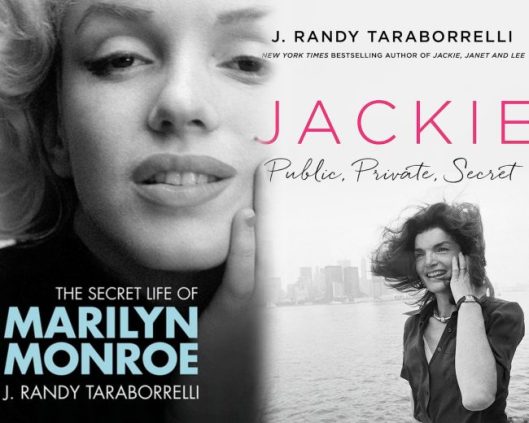

J. Randy Taraborrelli is a prolific celebrity biographer whose many bestsellers include The Secret Life of Marilyn Monroe (2009), later dramatised in a TV mini-series of the same name (see here.) And although she never met America’s First Lady, speculation about Marilyn’s association with the Kennedy brothers has recently generated headlines in media coverage of his latest book, Jackie: Private, Public, Secret.

Marilyn first appears in a chapter regarding Mrs. Kennedy’s televised tour of the White House, broadcast in early 1962. Jackie was unsure about appearing on television without her husband, Taraborrelli claims, and sister-in-law Ethel Kennedy (wife of Robert F. Kennedy) challenged her to an impromptu mock audition during a family gathering. After she spoke a few words, the president told his wife her speech was ‘very nice.’ Bobby and Ethel did not agree, however.

Perhaps it was nerves, but Jackie had adopted a tone that didn’t sound like her. Ethel turned to the others and asked, ‘Who does she sound like? I can’t put my finger on it.’ Bobby thought it over, snapped his fingers, and said, ‘Marilyn,’ to which Ethel said, ‘Yes. That’s it. Marilyn Monroe.’ Jackie was dismayed. ‘I do not sound like Marilyn Monroe,’ she exclaimed. Seeing that she was upset, Ethel then assured her that she’d be fine on camera, ‘as long as you don’t talk like that.’

This paragraph is typical of Taraborrelli’s style, in that he doesn’t report events so much as reimagine them. It’s unclear whom his source was for this story, though the chapter notes mention a 2017 interview with Leah Mason, described as Ethel Kennedy’s secretary; and a 2005 interview with starlet turned gossip columnist Nancy Bacon. (Incidentally, Jackie’s soft-spoken tone has often been compared to Marilyn’s, so her delivery may not have been as out of character as Taraborelli implies.)

In the next chapter, ‘Marilyn,’ Taraborrelli states that John F. Kennedy slept with her only once, at Bing Crosby’s Palm Springs estate where he spent a weekend in March 1962. Marilyn’s masseur, Ralph Roberts, claimed she telephoned him that weekend and put an unnamed friend on the line, whereupon the man asked for advice about his back problems.

Obviously, this is a second-hand source; and Roberts admitted he merely guessed the caller was Kennedy because of his Bostonian accent (although he added that Marilyn confirmed it in a later conversation.) On the Kennedy side, other guests have recalled Marilyn being there, but these anecdotes amount to little more than hearsay.

George Smathers, the former Democratic senator for Florida, was interviewed by Taraborrelli in 1999, and claimed to have discussed Marilyn with the president (known to his friends as Jack.)

Jack and I talked about her. He thought she was beautiful, but maybe not the smartest girl in the world. He liked her sense of humour and her playfulness. He said Jackie was more serious, and it was fun being with a girl who was … not.

If Smathers’ memory is accurate, then Kennedy clearly didn’t know Marilyn very well. In his 2018 book, Murder Orthodoxies: A Non-Conspiracist’s View of Marilyn Monroe’s Death, Donald R. McGovern investigated Smathers’ association with the Kennedys, noting that while the two men enjoyed chasing women together, they were increasingly at odds politically. Much to Kennedy’s dismay, Smathers had run against him as a presidential candidate in the 1960 Florida primary. After taking office, Kennedy questioned Smathers’ loyalty again when the Florida senator voted against him on Medicare and foreign aid.

In 1964, shortly after the president’s assassination, Jackie discussed his presidency at length with historian Arthur M. Schlesinger. In the audio tapes, made public in 2001, Jackie revealed that Kennedy was hurt by Smathers’ actions, but ‘didn’t want to stick it to someone who’d once been a friend.’ Schlesinger then remarked that Kenny O’Donnell, a secretary to Kennedy, despised Smathers (and Jackie agreed.)

While Jackie added that Kennedy ‘just wouldn’t ever, you know, finally say, “OK, you’re out,”’ McGovern concludes that “the time arrived during his short presidency when John Kennedy would not and did not associate with Smathers personally.”

In the next chapter, ‘When Marilyn Calls,’ Taraborrelli claims that Marilyn made contact with Jackie after the Palm Springs weekend.

In April of 1962, Jackie was in Hyannis Port [the Kennedy family’s Massachusetts compound] when the phone rang in her bedroom, she picked it up, and the breathy voice on the other end asked, ‘Is Jack home?’ Jackie said he wasn’t home and asked who was calling. ‘Marilyn Monroe,’ came back the answer. ‘Is this Jackie?’ she asked. When Jackie identified herself, Marilyn asked if she’d tell the president she’d called. Jackie asked what it was regarding. Marilyn said it was nothing in particular; she just wanted to say hello. A little stunned, Jackie said she’d pass on the message and hung up.

As Taraborrelli states in the chapter notes, author C. David Heymann made a similar claim in his 1989 book, A Woman Named Jackie, giving Kennedy’s brother-in-law, actor Peter Lawford, as his source. In this ‘apparently untrue story,’ Heymann claimed Marilyn had called Jackie at the White House. Heymann also alleged that Marilyn told Jackie she was in love with her husband, to which Jackie responded by sarcastically inviting Marilyn to give up her career and take Jackie’s place in Washington.)

While Taraborrelli doesn’t go as far in his claims, the story is essentially the same. Heymann was a controversial figure in the publishing world, with one of his books withdrawn from sale due to numerous factual errors. In 2014, his final, posthumously published book, Joe and Marilyn: Legends in Love, was comprehensively debunked in a Newsweek cover story.

According to Taraborrelli, Adora Rule (described as an assistant to Jackie’s mother) claimed that Jackie suspected her younger half-brother, Jamie Auchincloss, had played a prank, which he denies. Taraborrelli, who interviewed Rule and Auchincloss in 2021-22, adds that when Jackie passed the message on to Jack he dismissed it as a crank call, given that it was on their private line. Only a few people had this number, which makes it unlikely that – by Taraborrelli’s own account – Jack had shared it with a woman he hardly knew, beyond a possible casual fling.

Furthermore, the number was not included in Marilyn’s final address book, now owned by collector Scott Fortner. Nor, indeed, are there any entries for the Kennedys. However, it is known that Marilyn called Jack’s brother Bobby, the Attorney General, at the Justice Department a few times in June and July. They had become friendly via their mutual acquaintance, Peter Lawford – but Marilyn usually spoke to Bobby’s secretary, Gloria Lovell.

Furthermore, the number was not included in Marilyn’s final address book, now owned by collector Scott Fortner. Nor, indeed, are there any entries for the Kennedys. However, it is known that Marilyn called Jack’s brother Bobby, the Attorney General, at the Justice Department a few times in June and July. They had become friendly via their mutual acquaintance, Peter Lawford – but Marilyn usually spoke to Bobby’s secretary, Gloria Lovell.

In a third chapter focused on Marilyn, ‘The Madison Square Dilemma,’ Taraborrelli covers the Democratic fundraiser where she famously serenaded the president in May 1962. According to her husband’s Secret Service agents, Larry Newman and Joseph Paolella (interviewed by Taraborrelli in 1990, 2000-2001, and 2012), Jackie discussed the impending gala, and Marilyn’s planned appearance, with family members, including her mother, Janet Auchincloss, sister Lee Radziwill, and half-sister, Janet Jr., over lunch on the porch at Hammersmith farm, her childhood home on Rhode Island. (Jackie’s own Secret Service agent, Clint Hill, ‘had another duty’ that week, Taraborrelli writes.)

ʻIf I don’t go, how will it look?’ Jackie asked everyone at the table. ‘How will it look if you do go?’ was Janet Jr.’s response. Their mother felt Jackie should attend … Joseph Paolella said Janet felt that not facing the Marilyn situation head-on would only serve to feed the rumour mill, and then, as she put it, ‘the lie becomes the truth’ … Finally, after a half hour, the sisters walked toward the house. Once they were seated, Janet turned to Jackie: ‘So?’

Jackie said, ‘I’m not going. I think it’s just asking for trouble.’

Janet wasn’t happy about it. ‘This decision’s not noble,’ she told her. ‘It’s selfish.’ Jackie’s mind was made up, however.

The allegation that Jackie avoided the gala because of Marilyn also originates with Heymann, as Donald R. McGovern has noted. However, while Heymann erroneously stated that she spent the weekend of May 19th at another of the Kennedy homes in Atoka, Virginia (which was not fully built until 1963), Taraborrelli adds that she actually stayed at Glen Ora, their original Virginia estate. Citing Clint Hill’s 2012 memoir, Mrs. Kennedy and Me, McGovern argues that Jackie’s absence was neither remarkable nor related to Marilyn (one of many celebrities who performed that night.)

Agent Hill explained that the First Lady, who had recently entered the local Loudon horse show, planned to ride Sardar that weekend, and although President Kennedy wanted Jacqueline to attend the birthday gala and fund raiser in New York City, since his wife’s absence could be a political liability, he eventually consented to his wife’s wishes. Apparently the press was not informed of the First Lady’s plans and Agent Hill noted that she was particularly and especially happy. She despised political functions; and her absence there was commonplace, not surprising.

In a fourth and final chapter dedicated to ‘the Marilyn situation’ (titled, perhaps inevitably, ‘Happy Birthday Mr. President’), Taraborrelli mostly concurs with this view of a pleasant weekend at Glen Ora, but can’t resist adding a few insinuations.

As soon as they got there, Pat Kennedy Lawford – JFK’s sister, married to the actor Peter Lawford – called Jackie to tell her that any concern about Marilyn was blown way out of proportion. She explained that what was being planned was nothing more than ‘a harmless prank.’ Though one might think it odd under the circumstance, Pat was actually one of Marilyn’s best friends. She said she’d never allow her to do anything to embarrass Jackie. According to what Jackie later told a relative, she asked Pat, ‘Exactly what’s going on with her and Jack?’ to which Pat responded, ‘Nothing, Jackie. I swear it’ … ‘Maybe some people were whispering about Marilyn, but she wasn’t a main topic of discussion,’ said Larry Newman.

Taraborrelli turns to Marilyn’s performance at Madison Square Garden, which was only briefly noted in the press (TIME magazine published a photo of her onstage), while Jackie’s absence merited little comment. Only in later years, after the demise of Marilyn and the Kennedy brothers, was it considered an historic moment.

While Jack and Bobby were delighted about Marilyn’s act, others in the family felt uneasy about it. Ethel called Jackie at Glen Ora to tell her she felt the performance was ‘very disconcerting.’ She said she couldn’t understand why Jack authorised it. Jackie responded, ‘The attorney general is the troublemaker here. Not the president.’

The chapter ends with Marilyn’s death in August 1962. “Jackie was at Hyannis Port when Letitia Baldrige [her White House social secretary] called with the news,” Taraborrelli writes. In the chapter notes he lists Newman and Paolella among his sources, alongside fellow Secret Service agents Bob Foster (interviewed in 2000-02) and Lynn Meredith (interviewed in 2005.) He also refers to Laurence Leamer’s The Kennedy Women, and Monroe biographies by Anthony Summers, Charles Casillo, and Gloria Steinem.

Marilyn reappears later in the book, following Jackie’s second marriage to Aristotle Onassis. In 1971, Taraborrelli writes, Jackie’s mother found copies of Eros magazine inside her husband’s desk drawer. One of the magazines, published in the autumn of 1962, featured Bert Stern’s striking images of the late actress. (She had posed topless in some of the photos, originally shot for Vogue.)

Eros – named after the Greek god of love – was a high-priced, lavishly produced magazine of erotica that published just four editions in the 1960s. Its focus was the burgeoning sexual revolution. It was erotic, not pornographic. However, to a woman of Janet’s time and place, it’s not surprising that she would find them indecent.

After telling Jackie about them, Janet went to her room and, much to Jackie’s surprise, returned with the magazines. Also, perhaps to her surprise, one of them had Marilyn Monroe on the cover. It’s not known if Jackie was aware, but Bobby Kennedy had filed a lawsuit against the magazine’s publisher, Ralph Ginzburg, claiming he’d violated federal laws by publishing the seductive pictures of Marilyn … According to family members, when Janet asked if she should confront Hugh, Jackie advised her not to. ‘People should be allowed to have secrets. We all have them,’ she said. Jackie was also not the type to be forthright about sexual matters. ‘We were much too discreet and private in my family to talk about those things,’ said Jamie Auchincloss … Upon Hugh’s death, his son Yusha would discover the magazines. He gave them to Jamie, who still has them today.

As Jamie is listed in the chapter notes, he was likely the source for this peculiar story. Marilyn features more prominently in the next chapter, ‘Jackie’s Therapist’, as Taraborrelli reveals that Jackie underwent psychoanalysis with Dr. Marianne Kris after a chance meeting at a party hosted by Andy Warhol. Dr. Kris had previously treated Marilyn from 1957-61, when her decision to involuntarily commit Marilyn into Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic resulted in her being fired. According to Taraborrelli, Jackie’s appointments took place in the same office on Central Park West where Marilyn had regularly visited Dr. Kris. He relates an anecdote from an unnamed ‘New York patient’ who met Jackie in the waiting room.

At this same time, Norman Mailer was either getting ready to release or had already released a biography of Marilyn [published in 1973.] Everyone in New York was talking about it. I looked at the cover of the magazine Jackie was reading, and, sure enough, it was an article about the Mailer book with photos of Marilyn. I couldn’t help but stare for a moment. She noticed and looked up from the magazine and said, ‘So iconic.’ Just those two words. Then, she went back to her reading. It really struck me. I knew I’d never forget it.

Later, I had to ask Dr. Kris about it. She said she wouldn’t discuss Jackie, but she also said, ‘Don’t believe everything you read about President Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe,’ which somehow seemed significant.

Jackie was unaware of her therapist’s association with Marilyn, Taraborrelli writes, until she invited Dr. Kris to spend the weekend with her at Hammersmith Farm. Taraborrelli dates this visit back to the spring of 1971 (two years before Mailer’s book was published.) He admits it was unlike Jackie to invite a relative stranger into her family circle, adding that she wanted Dr. Kris to observe Janet, whom Jackie believed was experiencing memory loss. When Janet discovered this, she demanded Jackie and her guest leave immediately.

The consequences of Marianne’s unfortunate visit might’ve ended there had it not been for Yusha’s recognition of her name. At first, he couldn’t pinpoint it, but after making a few phone calls he remembered that Marianne Kris had once been Marilyn Monroe’s psychiatrist … Jackie was hurt and angry when Yusha told her about Marianne’s past. How could she have kept such information from her? ‘Everyone on the planet knows what I went through with Jack and Marilyn,’ she said.

When Jackie confronted her, Dr. Kris said she felt no responsibility to inform her about any former patients in the same way she’d never reveal that she’d ever treated Jackie. We don’t know a lot about their discussion only that Marianne asked, ‘How is this relevant?’ to which Jackie responded, ‘How is it not relevant?’

Hugh ‘Yusha’ Auschincloss Jr., who died in 2015, was apparently not interviewed for this book; but the chapter notes refer (yet again) to his step-brother Jamie, who may be Taraborrelli’s source regarding how the therapist’s prior link to Marilyn was discovered. The author then cites a 2022 interview with Dawn Morris, described as a student of Dr. Kris, regarding her failed treatment of Marilyn. She alleged that the psychiatrist believed Marilyn might still be alive had she stayed at Payne Whitney for longer (a view also shared by hospital staff.)

ʻDr. Kris wouldn’t apologise for having taken care of taken the best care of her patient,’ said Dawn Morris. ‘People don’t know she was also the one who recommended Dr. [Ralph] Greenson as her replacement. She believed in him at the time, though she later felt her trust had been misguided. Somehow, Dr. Kris and Jackie had worked out these issues, though I don’t know the details. Jackie did decide to continue as a patient.’

This chapter ends with Morris claiming Jackie raised the subject of Marilyn’s phone-call with Dr. Kris, who said Marilyn once told her she had placed a call to Jackie but didn’t speak to her. However, Taraborrelli earlier claimed they did speak briefly, and with all the main players long dead, the reliability of this story now rests on Morris alone.

Dr. Kris was fascinated by the fact that, ten years after, Jackie was still so moved by that call, even disturbed by it. But she told me Marilyn had that effect on people. ‘If you’d ever been touched by her or had any interaction with her no matter how distant, it somehow never left you,’ she said.

Jackie’s long struggle with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder was more fully documented in Barbara Leaming’s 2014 book, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis: The Untold Story. In marked contrast to Taraborrelli, Leaming – who also published a Monroe biography in 2000 – referenced the actress only once in relation to Jackie, who mentioned her death while confiding in a Jesuit priest in 1964, a few months after her husband’s murder.

By May 19th, Father McSorley found himself growing fearful that Jackie, as he wrote, ‘was really thinking of suicide.’ The priest had briefly hoped she might be doing better, but the way she talked now spurred him to take a different view. Speaking again of the prospect of killing herself, Jackie told him that she would be pleased if her death precipitated ‘a wave’ of other suicides because it would be a good thing if people were allowed to ‘get out of their misery.’ She disconcerted the priest by insisting that ‘death is great’ and by alluding to the suicide of Marilyn Monroe. ‘I was glad that Marilyn Monroe got out of her misery,’ JFK’s widow maintained. ‘If God is going to make such a to-do about judging people because they take their own lives, then someone ought to punish Him.’ The next day, after Father McSorley strove to persuade Jackie that suicide would be wrong, she reassured him that she agreed and that she would never actually attempt to kill herself.

1973 marked the tenth anniversary of Jack’s death, and five years had passed since his brother Bobby was also assassinated. According to Taraborrelli, Jackie marked the sombre occasion with Ethel Kennedy, who hosted a memorial mass at Hickory Hill, her Virginia home.

As soon as Jackie walked in, she saw a Ladies’ Home Journal on the kitchen counter with a winsome picture of Caroline [her teenage daughter] … She stiffened as she picked it up. Also touted on the cover was an interview with Eunice Murray, who’d been Marilyn Monroe’s nurse, and the serialisation of the re-release of Jim Bishop’s book The Day Kennedy Was Shot. ‘Why, Ethel?’ Jackie asked, dismayed. ‘Why?’ Ethel grabbed the magazine and said, ‘Oh, Jackie, you can’t take that stuff seriously. But then, just as suddenly, she burst into tears, her moods clearly all over the place. ‘Just look at us,’ she said as Jackie took her into her arms. ‘It’s so unfair. First Jack, then Bobby. Will we ever get over it?’

Taraborrelli’s source is Ethel’s personal assistant, Noelle Bombardier, interviewed from 2012-15. It’s easy to understand how the blanket media coverage of her husband’s death would have distressed Jackie. However, this is the third instance of a story based on a magazine article. By the mid-1970s, Jack’s affairs with Mary Meyer and Judith Campbell Exner had been exposed. These relationships were seemingly far more serious than his fleeting association with Marilyn; but due to her celebrity, the rumours endured.

Exner admitted she had been mob boss Sam Giancana’s mistress at the same time she was dating Jack, and conspiracy theorists have alleged that Giancana fixed the Democratic vote in Chicago during the 1960 election. It was reported that Exner had made more than twenty calls in a single year to President Kennedy, beginning in March 1961. Several of these calls were made from Giancana’s residence. (Giancana was murdered in June 1975, a day before he was due to testify before the Church Committee, as part of an investigation of covert intelligence operations.)

After the death of husband Aristotle Onassis in March 1975, Jackie resumed her career in New York, working as a book editor for Viking. That September, she contacted Frank Sinatra to discuss publishing his autobiography, but the deal fell apart in November, when the Exner story broke. Sinatra had been a friend of Sam Giancana, and his rumoured mafia connections dated back to long before 1960, when he publicly endorsed Kennedy’s presidential campaign.

As Attorney General, Bobby Kennedy had launched an attack on organised crime, and the president was advised to sever ties with Sinatra. He cancelled plans to visit Sinatra’s Palm Springs estate during the 1962 Democratic convention, staying with Bing Crosby instead. This was on the same March weekend when Marilyn was said to have been in attendance.)

Marilyn’s final appearance in Taraborrelli’s book comes in a chapter concerning John F. Kennedy Jr.’s reported fling with pop superstar Madonna in 1988, while she was still married to actor Sean Penn. Jackie is said to have disapproved of her son’s relationship with the singer, frequently compared to Monroe in the media. Taraborrelli discussed the matter with Jackie’s photographer friend, Peter Beard.

Jackie really didn’t know enough about Madonna to have an opinion about her artistry; she just took issue with antics she viewed as self-serving and attention-seeking … If Madonna reminded Jackie of Marilyn Monroe – as some writers have speculated over the years – it was only superficially. Peter Beard noted, in a 2016 email, ‘Because Jackie wasn’t familiar with Marilyn’s work, she could make no real comparison. All she knew of Marilyn was what she’d done to generate publicity. She once told me she never saw any of her films. She said it would never occur to her to sit through a Marilyn Monroe movie. The only thing she’d ever seen her do was the birthday song to JFK at Madison Square Garden, and she just thought it was sad.’

Maybe it was snobbery, but Jackie didn’t think Marilyn was that smart, and she felt the same way about Madonna. She knew little about what it takes to make it in show business, even after having known Frank Sinatra and Michael Jackson. ‘It wasn’t her world, and she wasn’t interested in it,’ says Peter. ‘She didn’t think it took brains as much as it was maybe just talent and exposure. Where Marilyn was concerned, I told her she was wrong and that Marilyn was smart, an intellectual.’

However, William Kuhn’s 2011 book, Reading Jackie – examining her publishing career at Viking, and later Doubleday – suggests that her understanding of Marilyn might have been more nuanced and sympathetic than Taraborrelli supposed.

Jackie worked on several Monroe-related projects, beginning in 1981 with Allure, a book of photography compiled by legendary Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, including a photograph by Bert Stern – from the same session that allegedly offended Jackie’s mother. “What did Jackie say to Vreeland about the Monroe photograph?” Kuhn pondered. “Probably nothing, but the fact that she silently allowed Vreeland to include it shows Jackie content to acknowledge Monroe’s ur–sexiness, a quality that Jackie did not think she shared with the screen icon.”

While Jackie and Vreeland were working together, a proposal came from Doubleday for a book featuring more images by Stern. (The Last Sitting was published in 1982.) ‘Marilyn Monroe!!!’ Jackie wrote in a memo to her colleague Ray Roberts. ‘Are you excited?’ “If injury there had been,” Kuhn speculated, “she was able to rise above it.”

David Stenn, who wrote an acclaimed biography of actress Jean Harlow under Jackie’s guidance. recalled his surprise when she raised the subject of Marilyn. “Jackie didn’t mention Monroe in the context of JFK but rather as part of a continuum with Jean Harlow: both of them were blondes who made their sexual appeal the centre of their screen personalities,” Kuhn reflected. “As with Vreeland, Jackie was willing to discuss Monroe with Stenn in a completely dispassionate, even admiring way.”

Jackie: Public, Private, Secret is Taraborrelli’s fourth book about the Kennedys, following Jackie, Ethel and Joan: Women of Camelot; Jackie, Janet & Lee: The Secret Lives of Janet Auchincloss and Her Daughters; and The Kennedy Heirs: John, Caroline, and the New Generation. Other related titles include Sinatra: Behind the Legend and Madonna: An Intimate Biography.

Reviewing Jackie, Janet and Lee for The Georgetowner in 2018, fellow celebrity biographer Kitty Kelley criticised Taraborrelli’s penchant for reconstructing events he did not witness personally, and questioned the credibility of key sources also featured in Jackie: Private, Public, Secret.

Nothing sells like books on sex, diets and the Kennedys. If you wrote ‘How JFK made love to Marilyn Monroe on 150 calories a day,’ you’d have an instant success. Just ask J. Randy Taraborrelli, who’s been mining two of those three veins for the last 20 years … In this book, some readers might be troubled by the lack of attribution for ‘she felt,’ ‘he thought,’ ‘said an intimate,’ ‘revealed an associate,’ ‘confided an employee’ and ‘reported someone with knowledge of the situation’ … If you’re a reader who requires corroborated information and credible sourcing in your non-fiction, this book will give you pause. Then again, if your requirements are less stringent, you might enjoy the photographs.

Kelley interviewed both George Smathers and Jamie Auschincloss for her 1979 book, Jackie Oh! When Smathers described President Kennedy’s sexual escapades in vivid detail, Kelley asked how the Florida senator could know unless he was there. Smathers chuckled. ‘Well, of course I was in the room with him …’

“While Jamie Auchincloss was not the source of the more controversial material in my book, he did speak openly about his famous relatives and, unfortunately, he paid a price,” Kelley added, noting that Jackie broke off all contact after the book was released. More recently, Auchincloss served time in prison for possession of child pornography. “I’ve always maintained that this surprising and unfortunate turn in Jamie’s life in no way impacts on his standing in history or his memories of growing up during the Camelot years,” Taraborrelli contends.

These unsavoury revelations cast a lingering shadow upon Jackie: Public, Private, Secret. Nonetheless, Taraborrelli’s string of bestsellers has proved that pairing the Kennedy brand with other iconic figures – no matter how tangentially – only expands his readership. Meanwhile, amid the appropriation of Camelot myths by the Alt-Right, another ‘Kennedy heir’ is making an unlikely bid for presidential nomination. And so history repeats itself, or as Jacqueline Kennedy once said of Marilyn Monroe: “She will go on eternally.“

You must be logged in to post a comment.